Uncovering Tribal Life in the Remote Corners of Northern Kenya

Article and photos by Lies Ouwerkerk

Senior Contributing Editor

10/28/2019

|

| Samburu warrior at "Sabache Camp," at the foot of Mount Ololokwe in northern Kenya. |

Kenya is the perfect travel destination for a host of reasons. It is one of the most popular countries to join a Big Five safari (rhino, lion, leopard, elephant, buffalo) or watch the spectacular wildebeest migration (July/ October). You can climb challenging mountains such as Mount Kulal or Mount Kenya — Africa’s second-highest mountain after Kilimanjaro, visit coffee and tea plantations in the Highlands, lounge on pristine white-sand beaches along the Indian Ocean, or learn about tribes still holding on to their traditional way of life in spite of ongoing modernization elsewhere.

There are more than 40 different tribes in Kenya, and they fall into three major ethnic categories. The Bantus, who once migrated from West and Central Africa, make up about 70% of Kenya’s total population and occupy the coastal, central, and some eastern and western regions of the country; the Cushites originally from Sudan, Ethiopia, and Somalia, include the Rendille, Gabbra, and El Molo people, and are mainly nomadic pastoralists; the Nilotes include the cattle-herding Maasai, Samburu, and Turkana — originally hailing from current-day Ethiopia.

The semi-nomadic Maasai people, traditionally known for their bravery with lions, are by far the most known tribe of all. Red-robed, tall, and slender, they call Maasai Mara National Park their home. They have become an international symbol of Africa’s tribal life, especially since various companies, including Louis Vuitton and Land Rover, have used their name and image, making them one of the biggest cultural brands on the planet.

The semi-nomadic Samburu, Rendille, Gabbra, Turkana, and El Molo people are far lesser known than the Maasai. They roam with their camels, goats, sheep, and cows the arid regions of Northern Kenya, between the Ndoto Mountains and Lake Turkana (world’s largest desert lake) as well as in the Chalbi Desert, northeast of the lake.

These remote tribes are the focus of a small expedition I joined for a couple of weeks in the company of four other adventurers and a guide/ driver, whom I all met in Nairobi, our starting point.

Camping

After a long day drive through Kenya’s Great Rift Valley, crossing the equator mid-day, and spotting ostriches and lesser flamingos along the way, our 4x4 veers off the highway to reach our first campsite near a riverbed, flanked by palm trees that provide the perfect cover from the scorching sun.

|

| Crossing Kenya's remote northern regions in a 4x4. |

Our accommodations have already been set up by Origins, a Kenyan safari operator specializing in wildlife and cultural heritage tours in Africa, and they do not disappoint. We have each our own tent, tall enough for standing, where a firm cot with real bedding promises some good night's sleep. There are also shower and toilet facilities, comfortable chairs and tables in a dining tent, and above all, a small kitchen team that makes wining and dining in the deep bush an unexpectedly classy and delicious affair.

|

| Campsite under trees in Kenya. |

|

| Dining tent in Kenya. |

Samburu People

For a few days, we explore the lands of the Samburu, semi-nomadic cattle herders believed to have split from the Maasai a few centuries ago. Since the government is trying to pressure them into settling down in permanent villages, some clans are also experimenting with small-scale cash-crop cultivation. A sedentary lifestyle in these arid regions is no mean feat. As a result, some Samburu men have found work away from their families, in the army and police force, or as guards for companies in big cities, thanks to their reputation as fearless warriors.

The Samburu ("butterflies") are the most northerly of the Maa speaking groups, and refer to themselves as Loikop — "those who have territory." They live mainly from the products of their herds, with milk and blood from their cattle (without killing them) being their main staple. Increasingly, they also acquire agricultural products with the money they earn from selling cattle — maize among others, from which they make porridge.

The elders of the polygamous Samburu play a very important role in their society. They decide who can marry whom, how many wives each member can have, and for what price.

Roles for Samburu men and women are clearly defined. Men herd cattle and protect their families. Women build huts with branches, dung, and mud, only to dismantle them when they move elsewhere. In case a man has more than one wife, each wife builds her own hut, for herself and her children. Women also collect firewood, milk cows, cook food, take care of their offspring, and do crafts like beadwork.

|

| Samburu woman. |

|

| Samburu warrior. |

The Samburu are one of the few Kenyan tribes that have been hanging on to their traditional tribal attire rather than giving in to Western-style dressing. They wear elaborate, colorful headdresses, beaded necklaces, bracelets, anklets, and paint their faces and hair with red ochre.

|

| Samburu necklaces. |

They love to sing and dance, traditionally without any instruments. Men and women usually dance in separate circles, with men often jumping high in the air — but they also dance some parts together.

|

| Samburu men and women dancing. |

Rendille People

|

| A Rendille woman. |

We also visit a village of Rendille people, whose lifestyle, like the Samburus’, revolves around their livestock. But what cows, sheep, and goats are to the Samburu, camels are to the Rendille. Camels serve various important purposes: they survive very well in the harsh regions around Lake Turkana since they can go without water for a very long time. They also supply the Rendilles’ main food — milk, and they can easily carry the Rendilles’ households in specially designed saddles when clans are on the move.

The Eastern Cushitic Rendille have historically maintained a good relationship with their Nilotic Samburu neighbors, to the point of adopting many of their customs, outfits, and language. Recently, considerable amounts of intermarriages have taken place between them, giving rise to a kind of hybrid culture. The tribes live according to a well-defined system, centered on age, in which every 7 or 14 years boys can enter into warrior-hood, and warriors can shift into elder-hood. At those ceremonies, boys are circumcised. They can then carry a spear as a symbol of manhood. Elders have their head shaven.

Rendille people exist in large settlements, with various clans living together. An established migration system ensures that each clan has sufficient access to water and green pastures. Rendille warriors may also live in temporary shelters far from their village, making it easier to let their animals graze. Here and there in the bush, Kenya’s government and NGOs have constructed central water wells to secure the survival of nomads and their cattle. There are also central water places in villages where people can fill their jerricans in return for inserting coins in meters.

|

| Woman with jerrycan on her way to a water well. |

Escorted by an armed ranger, we explore on foot some grass and bush land close to our campsite, where camel herds have been spotted lately. We get a chance to meet a few wandering Rendille herders and young boys who assist them. The strongest boys join warriors in the bush, while other youngsters go to missionary schools.

The centuries-old way of surviving in the bush is basic: drinking camel milk, complemented by meat from slaughtered goats they have included in their herds. Men and animals sleep in makeshift shelters made from acacia branches to prevent raids by rustlers or attacks from predators such as lions, leopards, and hyenas. During an evening campfire, warriors pass on stories and tribal customs to their sons.

|

| Villagers playing a game called bao. |

In the village, a tribal dance performance is arranged by our guide, the ranger, and the tribe elders. The word spreads quickly. Soon women from many other settlements, decked out in their most colorful attire, with their kids in tow, enter the village, and start dancing too. In the end, when our guide hands over the pre-arranged price to the village chief, a quarrel ensues between the various clans, all demanding equal pay for their contribution!

|

| Dancing Rendille women of northern Kenya in a trance. |

Turkana People

Just past the Lake Turkana Wind Power Project, the most efficient in the world for providing low-cost energy, with 365 turbines powered by the Turkana Corridor wind, we arrive in Loyangalani. This frontier town is a melting pot of various ethnic groups who each live in their own tribal zone, among them the Samburu, Rendille, Turkana, and El Molo tribes. The town was also the setting for John Le Carré’s novel "The Constant Gardener."

|

| Turkana settlement. |

The Turkana, who are thought to be descendants of the oldest tribal society in the world, can trace their origins back to the fearless Karamojong people of northern Uganda, who in turn might have migrated from present-day Ethiopia around 1600 AD.

|

| Turkana tribes people. |

Cattle are the core of the Turkana culture: it is their source of livelihood, providing food (milk and meat), as well as wealth when sold for money or bartered for grain or used as compensation for a bride. Raids on non-Turkana neighbors are common and seen as a way for young men to establish their reputation of bravery. Cattle skins are used for clothing, sleeping mats, bags, containers, and shelters.

We visit a Turkana settlement where men perform ritual dances, sporting bells around their knees along with impressive headgears with ostrich feathers — worn in the past by warriors who had killed someone, today used only for ceremonial purposes. When we finally move on, the men are so deep in their trance that they cannot stop dancing and continue a party on their own.

|

| Turkana men perform dances with bells on knees. |

El Molo People

On the shores of Lake Turkana, we find a cluster of small huts, made from palm fronds and acacia branches, inhabited by El Molo people. Neighboring tribes consider them “lesser people” for economic reasons: they do not own cattle, are not pastoralists, and rarely eat meat. El Molo people live on fish (tilapia, Nile perch, and catfish) from the lake, fresh, or dried (when ready for consumption, soaked in lake water to be softened and boiled).

|

| El Molo women display their crafts during our visit

. |

Nowadays, the El Molo are threatened by extinction, numbering only about 500 people. Poor nutrition, lack of medical facilities, and drinking salty water from the polluted lake are often blamed for their low population growth and life expectancy: 40 years is considered old. Inbreeding is a factor as well, although intermarriage with other tribes, mainly Samburu, is increasing. More and more people have abandoned their traditional dress and wear western clothing. Their original language became extinct in 1974 and has been replaced by Swahili and Samburu.

|

| El Molo boy. |

In the old days, El Molo fishermen were famous for hunting hippos and crocodiles, and anybody who had killed a hippo could expect a big feast and being decorated with a necklace of hippo teeth. This hunting practice was banned when Kenya introduced anti-poaching laws. Today, with the help of NGOs and the government, El Molo learn to cultivate some plants in this remote volcanic wasteland and have access to freshwater tanks.

Gabbra People

We drive further north towards Kenya’s border with Ethiopia through the desolate Chalbi Desert where most Gabbra clans live in small clusters. At an oasis, we see endless herds of thirsty camels getting an opportunity to drink. Camel herds still arriving make a quick last run to the waterhole.

|

| Camels drinking water at an oasis in the Chalbi desert. |

In the middle of nowhere, a Gabbra woman carrying two little children signals us to stop. One of the kids has a big burn on his foot and is obviously in a lot of pain after walking into an open fire the evening before. “Can you please cure him?” she begs. Although we do leave them the antiseptic cream from the first aid kit, we do feel quite powerless.

During our visit to the Nomadic Girls School in Kalacha, where 450 girls in neat uniforms receive education in social studies, math, science, and English, we learn that it is extremely difficult to enlist teachers in this barren location and that at least six girls have to share a desk for two students. Unfortunately, there are not enough funds or space for more desks, nor extracurricular activities like sports. The girls come mainly from marginalized communities, but the school also offers refuge to runaway girls who discovered they were about to be married off to much older men for the customary price of three camels.

One of our travelers is a magician, and treats the kids, with great success, to some of his magic tricks. When he repeats his act in front of an adult Gabbra gathering, some women run away, screaming, afraid that he will put a curse on their community…

|

|

|

| Our magician showing his tricks to a spell-bound audience. |

Samburu Game Preserve

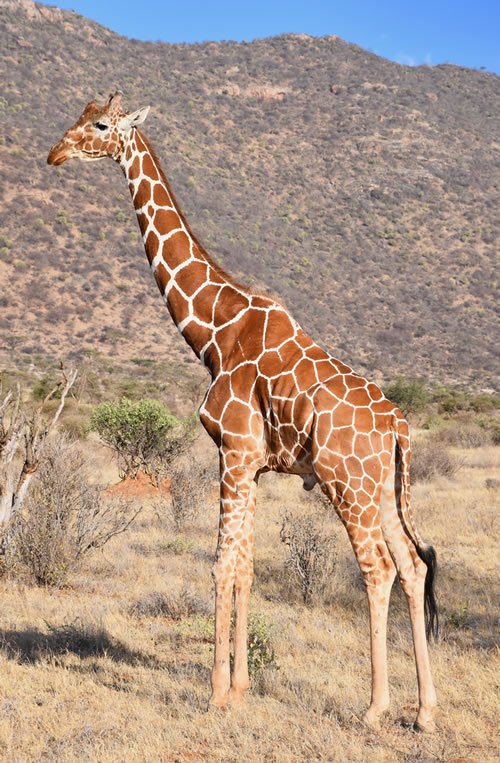

On our way back to Nairobi, we enjoy a full day excursion in Samburu Game Preserve, home to species rarely seen elsewhere, such as the reticulated giraffe, beisa oryx, and gerenuk, as well as to more widely observed cheetahs, lions, leopards, elephants, and buffaloes.

|

| Reticulated giraffe in Samburu Game Preserve. |

|

| Oryx in Sumburu Game Preserve. |

|

| Mother with young in Samburu Game Preserve. |

Overnight we “glamp” in beautiful Sabache Camp, a well run, community-owned (by impeccably groomed warriors) lodge whose funds help support the nearby Samburu villages, schools, healthcare programs, as well as clean water and emergency food distribution projects during droughts.

|

| Samburu girl herding cattle. |

Nairobi

Keen to learn more about current social impact initiatives, I stay a few days in Nairobi for the following worthwhile experiences:

-

With former street children, I explore downtown Nairobi while listening to their life stories and sharing a local lunch with them

-

With Agnes Kalyonge, a self-taught cook, and founder of a website with Kikuyu recipes, I scour a local market, followed by a cooking class and traditional lunch at her home.

|

| Sylvester, Jacktone, and Denis: promising Kibera youngsters serving as role models for a next generation . |

For More Info

The Lake Turkana expedition is offered by Native Eye Travel.

Lies Ouwerkerk is originally from Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and currently lives in Montreal, Canada. Previously a columnist for The Sherbrooke Record, she is presently a freelance writer and photographer for various travel magazines.

|