Kora Sounds from the Griot Compounds

The Gambia

Article and Photos by Lies Ouwerkerk

Senior Contributing Editor

|

|

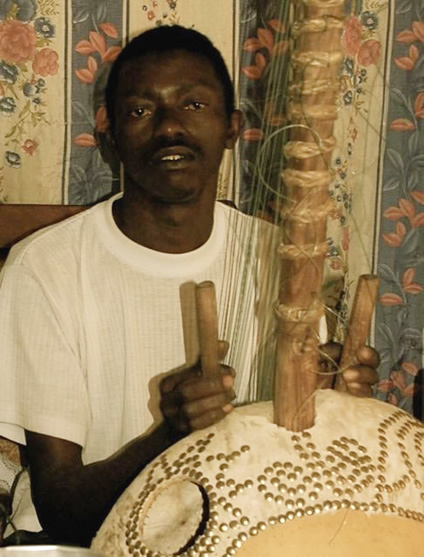

Pa Bobo Jobarteh with his Kora.

|

West Africa has an enormous diversity of peoples, each with their own customs, language, and traditions: the Bambara, the Bobo, the Mossi, the Dogon, the Fula, the Lobi, the Wolof, the Tuareg, and the Mandinka, just to name a few.

The Mandinka tribes, originally descendants of the Empire of Mali, have spread across most West African countries since the days of the Empire's first ruler Sundjata Keita, and today belong to West Africa's largest ethno-linguistic group, the Mande. But it is only in The Gambia, Africa's smallest country, that the Mandinka form the largest ethnic group within one particular country.

Most Mandinka live in family-related compounds in traditional rural villages led by a chief or a group of elders. Farming has always been their predominant occupation. Today, nearly every Mandinka in Africa is Muslim, although an admixture of Islam and traditional rituals are still fairly common in the countryside.

Although at least half of The Gambia's Mandinka population can read the local Arabic script — which is taught in small Koranic schools — their literacy rate in Roman script is rather low. Only in the coastal areas of The Gambia's Western Division — where tourism is a considerable source of income — young people attend schools with Western education more regularly, with English as the official language. But most Mandinka still live in an oral society, with an oral history tradition dating back hundreds of years, passed on from one generation to the next through songs, proverbs, and stories by members of griot families with famous surnames such as Konte, Suso, Jobarteh, and Kouyate (the first griot). For centuries, these were the traditional historians, genealogists, praise singers, war rousers, whistle blowers, advisors, arbitrators, buffoons, gossip mongers, satirists, news reporters, and political commentators. Only those born into the griot caste could become a jali, and unlike their fellow tribe members, they did not have to work the fields or fight.

The musical instruments most often used to accompany these singing or story-telling troubadours were the balafon, a type of xylophone, the kora, a string instrument with a sound resembling that of a harp, and the bolonbata, also known as the kontigo, which is actually a variation of the kora, only with less strings and a bent neck. It is especially the kora, however, that has become the hallmark of traditional Mandinka musicians over the years, and although the instrument has lost most of its original importance with the passage of time and the arrival of radio, TV, cinema, and telephone, the kora is still frequently used to entertain people or add luster to a formal ceremony or political campaign.

At Bird Safari Camp, deep in the bush of Central The Gambia, I have my first encounter with a traditional kora player. The performer is nobody less than master-player and singer Basuru Jobarteh, member of a most renowned traditional griot family. He lives part of the year in JangJang-Bureh, up the Gambia river, and spends the remaining months with his young Swiss wife — the harp player Rebekka Ott — in Winterthur. I am definitely in luck, as he has just returned from an extensive tour through India, where he has held concerts together with Indian sitar virtuosos, and has presented a kora workshop in Goa.

|

|

Basuru Jobarteh playing the Kora.

|

Basuru holds the kora vertically between his legs while playing seated, and he uses only the index finger and thumb of both his hands to pluck the 21 strings — 11 with the left, and 10 with the right hand. With the remaining six fingers he holds two vertical sticks on each side of the strings to secure the instrument.

Along with the melodious tunes on his kora, Basuru sings in his native language about the deeds of famous heroes and warriors of the past, about the traditions of his tribe, and about the societal changes of modern times. And during the intermissions, he is more than willing to show the instrument from up close to his audience. The body of the kora is made from half a calabash, hollowed out and covered with a piece of cow skin that is stretched over the open side and attached to the calabash with drawing pins, arranged in beautiful designs. The strings are made of nylon fishing wire and are attached to both sides of a long wooden pole. A sound hole in the side of the calabash also serves to collect tips, as most jalis don't charge a set fee for their engagements and are financially dependent on the appreciation of their audience.

A week later, luck strikes again in the small village of Gunjur, on The Gambia's west coast, when some local kids guide me unerringly to the compound of master-players Lamin Suso and his son Jali Madi Suso. They are the main breadwinners for at least 33 family and extended family members who barely make ends meet building and selling koras, teaching kora classes, and playing at local ceremonies such as weddings, circumcision and naming rituals, festivals, parties for those returning from abroad, or for tourists. Although they have no recordings to their names and are unknown outside The Gambia, they are undoubtedly big stars in their own community.

|

|

Mandi Suso with his Kora.

|

As is common among traditional griot families, Jali Madi took up the kora at a very young age, with his father as his main teacher, who, in turn, learned the trade from his father. Because of the intense study involved — the instrument, the melodies, the rhythms, and the large quantity of centuries-old repertoires of family and village history — Madi did not attend regular school like his siblings, and is now dependent on one of his younger brothers for the written word.

At the time of my visit, father and son are extremely busy building new koras, because, as Madi explains, they can only be constructed in the dry season from mid November to April. In that period, cowhides soaked in a bath of chemicals to soften the leather, and subsequently stretched over the calabash, can dry in the sun and shrink to fit very tightly over the calabash.

Close to Gunjur lies the rural town of Brikama, breeding ground for many other talented young jalis. One of them is the famous Pa Bobo Jobarteh, whose well-known Peace, Love, and Unity was once chosen as most favorite song by President Jammeh. Pa Bobo started gaining international fame after playing at the UK's Womad festival at age 11. Previous to that first international concert, he was "discovered" at the family compound in Brikama, where festival organizers paid a visit to his father and uncle, both famous kora players at the time, and accidentally heard him play. Since then, Pa Bobo has become The Gambia's most popular young kora musician. When I call him for an interview at his compound, he spontaneously invites me for a family lunch that very same day.

|

|

The famous Pa Bobo Jobarteh flashes his smile while playing his Kora.

|

Pa Bobo also has to feed a large group of family members, all living in their Brikama compound, and it is sobering to learn how even celebrities like him lead relatively restricted professional lives. There is no studio, there are no royalties, and there is no agent to promote him or other talented members of the Jobarteh clan. In The Gambia, and especially Brikama, Pa Bobo is a much admired and celebrated idol, as I find out during our little tour through town afterwards, but abroad he is still dependent on the contacts he has made haphazardly over the years. When we discuss the power of the computer these days, he frowns. He has to rely on his brother for surfing the Internet or exchanging email messages, and the brother has to resort to a slow computer at an Internet cafe in Brikama's market place.

After a traditional communal meal from one big bowl on the floor, Pa Bobo gives a flawless performance in his tiny guest room, singing about peace and the injustices many women still face in his society — a topic that is close to his heart, having two teenage daughters himself. As a true acrobat, he even plays the kora on his back, blindly touching all the right strings.

|

|

Pa Bobo Jobarteh paying his Kora on his back.

|

"I absolutely don't want my culture to fade away", he emphasizes when we bid our farewells. "We jalis have to do everything possible to keep the traditions of our people alive, for all generations of Mandinka still to come. That's why I play, sing, and memorize as often as I can..."

Lies Ouwerkerk is originally from Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and currently lives in Montreal, Canada. Previously a columnist for The Sherbrooke Record, she is presently a freelance writer and photographer for various travel magazines.

|