Visiting the Tribes of Madagascar

Article and photos by Lies Ouwerkerk

Senior Contributing Editor

11/2015

|

| From the market in the town of Ambositra, at the center of Betsileo territory in Madagascar. |

Madagascar, the fourth largest island in the world, sits in the Indian Ocean at a mere 250 km (150 mile) distance from the southeastern coast of Africa. In spite of its proximity to the African continent, most of the 22 million people living on the island can trace their genetic history back to Austronesian heritage.

The exact circumstances of the island’s first settlement, some 2,000 years ago, are unknown, but it is generally assumed that it was the result of a one-time event, possibly a shipwreck of ocean faring people originating from Indonesia, rather than of a deliberate mass migration. Various studies show that most of the 18 Malagasy tribes, especially those living in the Central Plateau, share the same linguistic, cultural, and physical characteristics found in populations of South Borneo and the Sunda islands. Coastal tribes also show affinities with some African populations, due to slave trade, intermarriages, and voluntary migration.

|

| Central Plateau where many of the various tribes in Madagascar live. |

A Guide For The Ride

Getting around in Madagascar, with a public transport system that is known to be unreliable, slow, or non-existent, can be very challenging, so finding a good driver is key.

The owner of my B&B introduces me to Solo, a retired schoolteacher turned driver, who speaks French fluently and is highly knowledgeable about the tribes of his country. He also has contacts all over the island, which will come in handy when we have to arrange access to the more remote, pastoral tribes.

Given that my 2 weeks availability will be too short to cover the whole island, Solo suggests we take the R(oute) N(ationale) 7 south, where the largest variety of tribes will be found. To reach them, we will have to branch off into dirt roads, and hiring a 4x4 is therefore a must.

|

| Map of tribes of Madagascar. |

The Merina

|

| Red earth dwellings in Merina land. |

Solo belongs to the largest ethnic group on the island, the Merina ("those who always come back home"), concentrated in the northern part of the central highlands, especially around the capital, Antananarivo.

Merina nobles reigned over the Kingdom of Madagascar until the French colonized the island in 1879 and ruled it until Independence in 1960. A large part of today’s educated middle class is Merina, but many are also subsistence farmers cultivating rice, Malagasy’s main staple, and other crops such as coffee, cotton, cassava, sweet potatoes, corn, and bananas.

|

|

| Agriculture is the central source of income in Madagascar. |

Most Merina converted to Christianity after the arrival of missionaries in the early 19th century, and following the example of their queen Ranavalona II in 1869.

Madagascar is among world’s poorest countries, and it shows especially in the capital: decrepit buildings, potholes in the roads, huge garbage piles left forever in the streets, kids climbing barefoot over the rubble heaps, panhandlers on every corner. The average Malagasy makes approximately $1 a day, and about 70% of Malagasy suffer from malnutrition.

According to Solo, there are many factors contributing to Madagascar’s poverty: lack of infrastructure (RN7 is one of the only two “paved” roads on the island), proneness to natural disasters like droughts and cyclones, corruption of government officials, political crises followed by international sanctions, limited access to credit, geographical isolation, a deplorable educational system, large scale deforestation, and antiquated, traditional farming and industrial techniques.

I observe some signs of the latter as soon as we leave the capital: oxen driven carts plow through rice paddies in the valleys, and the practice of "shifting cultivation" (temporarily cultivating plots, abandoning them after harvest, then burning their natural vegetation later to make the plots usable again), although now illegal, seems still widely practiced.

When we visit a metal pot factory in one of the small market towns along RN7, I learn that the entire process of melting used metal at high heat and remolding the material into big pots, is done manually. Young, barefoot men work long hours in a confined area, under extremely unhealthy conditions, in exchange for a very meager income and a bowl of rice.

|

| Young men work long hours barefoot for rice. |

The Betsileo

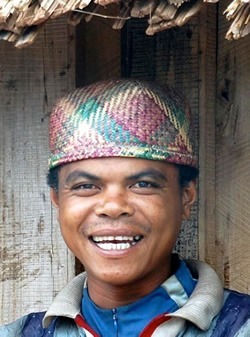

Advancing South, we slowly leave the land of the Merina, and enter Betsileo ("the invincible") territory, as is noticeable by the elaborately coiffed hairdos of women and girls, and the colorful, hand-made straw hats with which the Betsileo distinguish themselves. The Betsileo are especially famous for their neatly kept mountain slope rice paddies, and are considered the best farmers of Madagascar.

|

|

| People of the Betsileo tribe. |

The Betsileo are also well known for their traditional, periodic exhumation, re-wrapping, and reburial of the dead, called famadihana ("turning the bones"), practiced in agricultural off-season, the months of July and August. Although most of the Betsileo, like the Merina, converted to Christianity, many old beliefs still exist. For instance, ancestral spirits are thought to be around, and actively concerned with the fate of the living, so showing them respect and gratitude is of major importance. Funeral and reburial practices are festive, can last for days, and are accompanied by dancing, singing, and drinking.

Herbalists who remedy illnesses, and astrologers who calculate auspicious dates for important events such as ceremonies and agricultural activities, are also a prominent aspect of Betsileo traditions.

In Ambositra, a market town in the center of Betsileo territory, I sleep in a small wooden house, with a beautifully carved door full of traditional geometric motives and images of daily life, typical for this region, famous for its woodcarving.

|

| A "school bus" in Ambositra. |

The Zafimaniry

The real masters of woodcarving are the Zafimaniry, a tribe split off from the Betsileo centuries ago. Previously living in an impenetrable forest, totally isolated from the world until about six decades ago, they are now spread over a series of small villages in a partly deforested region, East of Ambositra. Trees play an important role in Zafimaniry’s lives: they live in wooden houses, their medicines are powdered mixtures of different woods, they warm themselves at wood fires which also dry and preserve their main staple maize that is hanging from the rafters of their houses, and in the old days they even wore clothes woven from bark fiber. Their wood crafting knowledge and their abstract patterns full of spiritual and mythological symbolism were in 2003 added to the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

|

| One of the abstract Zafimaniry woodcarvings. |

Their largest village, Antoetra, is still the only one accessible by car. To reach the other villages — Ifasina, Faliarivo, Fempina, Sakaivo, and Tetezandrota among others — one has to follow a steep walking trail, and be accompanied by a local guide / translator.

When we finally arrive in Antoetra, after a hazardous ride over a narrow dirt road full of enormous holes, a delegation of villagers is already awaiting us, not only to welcome the vazaha ("foreigner"), but also to collect money for entering the village and the services of local guide Joseph, and to promote their wood-crafted objects. Time did not stand still since the discovery of the Zafimaniry in the 1950’s, and tourism has obviously made its entree into Antoetra!

|

| Children's greetings in the village. |

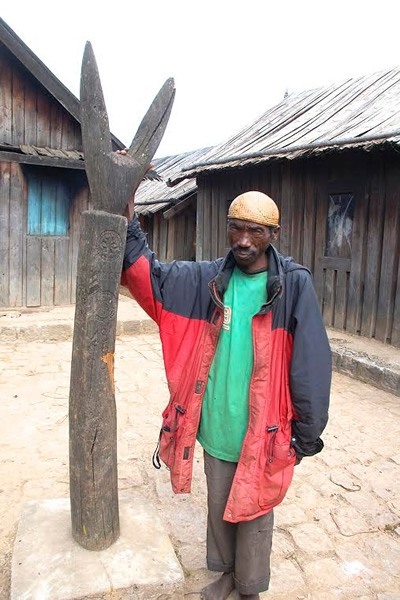

Joseph leads us via a narrow path along rectangular wooden houses, with peaked roofs and elaborately decorated shuttered windows and doors, to the home of the village chief.

|

| Joseph, the local guide in Antoetra. |

Seated on the floor, we are officially welcomed and given permission to wander around the village, albeit after handing the chief yet another fee. Then it’s up to Joseph’s modest home where we find his young daughters pounding rice in the living quarters. The most sacred part of the living room annex kitchen, is the northeast corner. Here, prayers, benedictions, and offerings of rum, honey, and incense take place at ceremonies like weddings, funerals, and births. Repeating an offering ritual 6 times brings luck, Joseph explains, but you really have to count carefully, for number 7 spells disaster.

|

| Joseph's children pounding rice in their modest home. |

The Tanala

|

| A house in the Tanala land. |

Driving further South on RN 7 towards the town of Fianarantsoa, we now enter the rain-forest of Ranomafana National Park, created in 1991 after the golden bamboo lemur was discovered here.

With a guide named Hery, I hike through the hilly, densely forested, foggy area and spot a couple of lemurs, the island’s chief mascots, endemic to Madagascar and highly endangered. Just outside the park, we also visit the tiny hamlet of Kelilalina, where we meet a clan of the Tanala ("people living inside the forest"), secret keepers of all traditional plants and their medicinal use.

Hery suggests we arrive early at the village, because it is harvest time, and most villagers have to work on the land outside the forest. But some are obviously stalling, because our highly anticipated thank-you present, a bottle of local rum, will be divided among all present.

In the village elder’s home, plastic mats are rolled out over the mud floor, and a group of about 30 villagers and their children sit down in silence, in anticipation of the elder’s speech. After he shyly mutters a welcome in a muffled voice, and Hery has returned some words of gratitude on my behalf, an assistant goes solemnly around with one single cup, and offers each villager a sip. Then the bottle is returned to the village elder, who slugs down the rest in one gulp.

In keeping with their religious traditions, the Tanala, another subgroup of the Betsileo, only take from the forest what is needed for survival, and adhere strictly to the rules of fady ("ancestral taboos" to placate the spirits and ensure their approval). There are days one cannot hunt or fish, for instance, and the consumption of certain animals, like the lemur, is off-menu altogether. Most lemur species are considered protectors, or even ancestors of a clan, whose spirits got lost in the rain-forest and therefore turned themselves into lemurs in order to survive. A few species, among them the nocturnal aye-aye lemur, however, are blamed for things that go wrong, and are particularly seen as a bad omen when spotted walking through the village.

The Bara

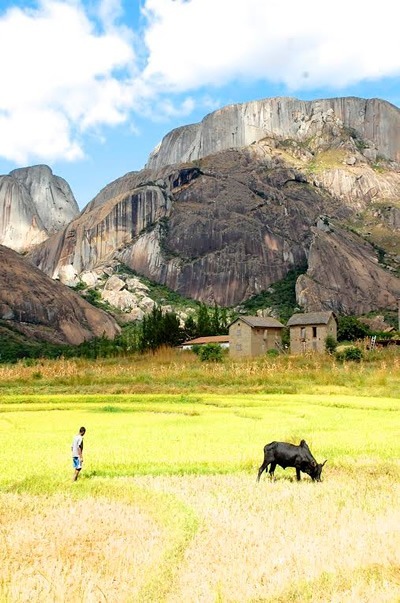

Around the Isalo Massif, further South towards Toliara, lies the land of the Bara ("those of the interior"), a zebu herding, trading, and raiding tribe that historically lived a semi-nomadic life style, and was organized in many affiliated kingdoms. In this strongly patriarchal tribe of clear African descent, polygamy is still fairly common. Other distinct features of the Bara are cattle rustling, practiced by young men before marriage to prove their manhood, and burying the dead in caves in the hills rather than in family tombs.

|

| Bara land with herder. |

We are accompanied by Vincent, a previous protégé of Solo, who took him for a year under his wings when 14 years old, orphaned, and completely illiterate. In the capital, Vincent learned to read, write, and speak French fluently, and eventually became a successful tourist guide in nearby Isolo National Park.

Vincent brings us to the hamlet where he grew up, and introduces us to the king of his Bara clan. The welcome is enthusiastic, and since the king speaks French, we can have a direct conversation. He explains that there has just been an attempted bandit raid on their zebus, so they are now building a high, protective wall to safeguard their most valued possessions. Each night, the animals are led into the corral, which will be hermetically closed off from possible invaders. Living so isolated certainly makes them vulnerable, and there is no confidence in those who should protect them, as these are the very providers of guns for the bandits.

|

| King of a Bara clan. |

Another concern is the school, which was recently built in cooperation with a NGO. Unfortunately, the teacher left, and so far, no substitute has been found in this sparsely populated land. That, of course, comes in handy for some parents, who use their kids as labor, especially during harvest time.

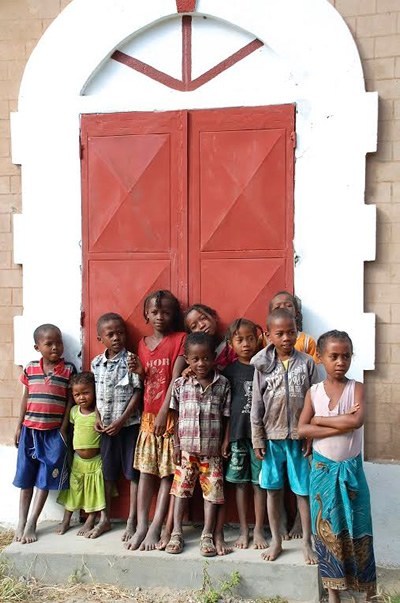

|

| School is closed now for the children. |

After our farewells, we slowly make our way to the car, followed by a string of jubilant, mostly barefoot children, holding our hands or just frolicking around. None asks for pens or candies, none has stretched-out hands. Once out of sight, the image of their innocent, happy smiles, against the backdrop of the imposing Isalo Massif, their modest homes, and their grazing zebu herd, will still be with me for a long time after.

|

| The children say goodbye. |

Madagascar Essentials:

- Background information on the island of Madasgascar.

- Malagasy and French are the main languages in Madagascar.

- Credit cards are only accepted in major hotels, so cash money is the way to pay. There are ATMs in the bigger cities, but the maximum amount that can be taken out equals $100 per day

- Average daily costs: dinner: $4-$10; middle class hotel: $30-$40; guide: $30; 4x4: $45. Additional charges are often not necessary, as many hotels offer free accommodation and meals to drivers

- An entrance permit for 30 days can be obtained at arrival in the airport, free of charge. Proof of a yellow fever inoculation within the previous 10 years, needs to be shown

- The lovely B&B "Chez Aina" — a true oasis in the crowded downtown area of Antananarivo — is a great start and finish to your trip!

Lies Ouwerkerk is originally from Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and currently lives in Montreal, Canada. Previously a columnist for The Sherbrooke Record, she is presently a freelance writer and photographer for various travel magazines. |