Adventures Along Mauritania's

Ancient Caravan Routes

Article and Photos by Lies Ouwerkerk

Senior Contributing Editor

|

|

Camels walking through sand dunes in Mauritania.

|

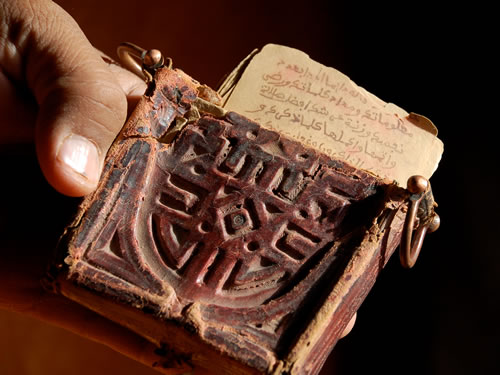

Mauritania's desert — which covers over 80% of the total land surface — is a true El Dorado for desert aficionados. In the white, ochre, and orange-colored sand dunes that alternate with brown and black mountains, plateaus, and green palmeries, the sound of silence is largely all you hear. At moments you expect it the least, you may suddenly have a fascinating encounter with a lone nomad or camel driver. After sundown, when the reddish sky has turned dark, the countless stars make you feel humble and awestruck, night after night. And hidden amidst the dunes lie the remnants of the ancient trading and religious centers of Chinguetti and Ouadane in the north, and Oualata and Tichitt in the southeast — all four included on the World Heritage List since 1996. Although they are now a far cry from their original splendor, their libraries still house impressive collections of centuries-old manuscripts.

|

|

Ancient manuscript.

|

Logistics

Traversing the remote Adrar and Tagant regions is — even by 4WD — certainly not for the faint-hearted. Distances are long, the sun can be unforgiving when there is no shade in sight, hotels and restaurants are non-existent, thorny shrubs can leave painful memories, and navigating through the loose sand can be extremely tricky and confusing, especially after sand storms have erased any previous tracks or the sand dunes have shifted. To survive and enjoy this ambitious circuit, it is essential to be accompanied by a truly experienced desert guide and to use a vehicle that is in excellent condition, equipped with plenty of extra gasoline and water. Also indispensable are basic foods, mats, sleeping bags, extra blankets for cold nights, matches, maps, a GPS, and if possible, a satellite telephone for emergencies. Driving at night and walking barefooted is strongly discouraged.

|

|

4WD tire wheel stuck in sand.

|

Traveling as a Single Female Traveler

As a single female traveler, I had asked for "a knowledgeable desert guide who could be trusted in all respects" at a recommended travel agency in Atar.

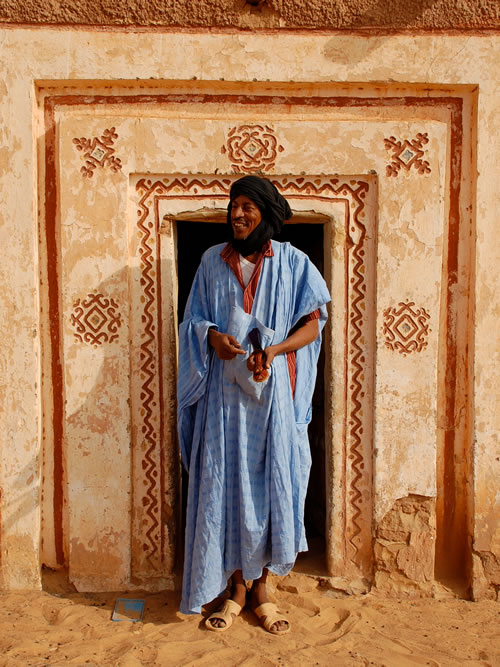

And there he is, picking me up at the Mauritanian-Senegalese border town of Diama: Sidi Mohamed ould Mohamed Lemine, or simply Sidatty, a tall and slender man in his late 30's, dressed in a white hawli (a long turban, skillfully draped around the head for protection against sun, wind, and sand) and an impressive light-blue boubou (a long wide robe made of beautifully embroidered damast). For the next three weeks, Sidatty will become my indispensable Jack-of-all-trades: driver and mechanic, shopper and bookkeeper, tent pitcher and cook, nurse and watchdog, storyteller and interpreter, and above all, my sole travel companion. And there is an added bonus: besides his native Hassaniya Arabic, Sidatty speaks French fluently — so this will be the perfect opportunity to spruce up my rusty French conversation skills.

|

|

Mauritanian man in blue robe standing in a doorway.

|

Rituals

Right at the border crossing, I already have my first encounter with a most important Mauritanian ritual that will become a standard fixture during our expedition. A friendly customs officer, who proudly recites the foreign word for driver’s license in 22 languages, invites us to raise a glass of tea for peace for all nations in the world. Preparing tea, the essential drink to seal a friendship or show hospitality in a country where consumption of alcohol is forbidden according to Islamic law, involves a number of obligatory stages. First, sugar and mint are added to a kettle with boiling water and the mix is brewed for a while on a small burner. Then the kettle is lifted high in the air to pour the liquid various times into miniature glasses and back again into the kettle in order to make it foamy and frothy. Finally the tea is tested for taste, sweetness and temperature — all before finally being served to the guests. After the glasses have been emptied in one gulp, they are washed again, followed by two refills. After the third glass, it is polite to wait for the tea maker to clean the tray and gear, and then leave immediately after. Later, I will discover that the tea ritual mainly belongs to the male domain, and that even small boys know already how to follow the right steps.

The well-asphalted Route de l'Espoir runs through the Sahel from west to east, along agricultural centers such as Ayoun Atrous, Kiffa, and Nema, where cafes and the small shops of butchers, bakers, artisans, and greengrocers line the narrow streets. Most Mauritanian houses are basic and colorless structures built of cheap materials, and litter is often dumped in the streets. But the sight of the men in their bright blue boubous, and the women with their pastel-colored melhafas (veils), graciously draped around their head and over their sleeveless low-neck dresses, easily makes up for the lack of eye-catching architecture and the rubbish everywhere. Women enjoy a relatively high degree of freedom in Mauritania in comparison to other conservative Muslim countries, and they are generally well respected. Some chubbiness is valued, and especially in rural Mauritania, the traditional force-feeding with cow milk and greasy foods is still practiced. "The woman is worth the place she occupies on the bed" is a common Mauritanian saying.

|

|

Men in robes gathering outside a shop.

|

The Occasional Material Favor is Requested

Police controls are rampant along the Route de l'Espoir, and at every stop Sidatty has to hand forms with our personal data, shake hands with the officials, and engage in the endless formal greetings back and forth which are so common in Mauritania: "how are you, where are you coming from, where are you going, how are your wife and children, what is the name of your father, how are your parents doing, etc. etc.". By the time the exchange is finished, it is quite common for the officials to ask for some favors: a cigarette, some money, a present, forwarding a message or a package to someone in another part of the country, or a lift to the next police post, on top of our luggage.

In Nema, where we will branch off into the real Sahara, we have to check in at the local police post with our documents. Past a group of tea-sipping and TV-watching officials stretched out on an iron bed that serves as a couch, we are led into a tiny office. The windows are completely plastered with pages of a yellowed 2001 calendar, and over the concrete floor, a mouse runs up and down from one corner to another. A grinning, toothless officer gestures us to take place on the plastic, totally ripped-open seats in front of his desk, carefully studies our documents — upside down — all with an air of great importance, and then stamps an empty page without further ado.

Although in the middle of nowhere, Oualata, a former trading center and in its heyday more important than Timbuktu, is a hidden gem not to be missed. In this town, where for centuries pilgrims from west Africa used to convene before traveling on to Chinguetti — the departure point for the annual pilgrimage to Mekka — where important scholars taught in world famous Koran schools, and where many caravans with gold, ivory, and salt used to stop on their way to all quarters of the world, I am stunned by an architectural style not seen in any other Mauritanian town. Doors, windows, and porches of box-like houses with reddish-brown facades are trimmed with traditional white designs; their white inner courtyards, in contrast, display decorations in red paint, often the same simple patterns drawn on the feet and hands of Mauritanian women. Nobody knows exactly where these traditional patterns originate from, although some sources suggest Byzantium, Ghana, and the Orient. Every fall, after the rainy season, the houses are repainted and skillfully decorated by the women of Oualata, with the help of a generous grant from Spain.

Encountering Nomads

On the rare occasions we see nomads in the vast Tagant desert beyond Oualata, with whole families run out of their tents as soon as they spot our vehicle from far. By the time we reach them, the reception committee has already lined up, and showers us with enthusiastic greetings, as well as with requests for aspirins, painkillers, ointments, facial cremes, Tshirts, jewelry, candy, or pencils. In the case of sick or wounded people, the need is often all too real, since doctors and nurses are few and far between. But more often their demands are just a reflex to seeing a foreigner, who is invariably regarded as a dispenser of goods and presents.

|

|

Two male camel herders welcome us.

|

Nomads live primarily on the milk and meat of their goats and camels, on self-made bread, and on non-perishables such as rice, pasta, sardines, cookies, and cans with vegetables, which they purchase a few times a year during their rare visits to the nearest town. Much more pressing than their need for food, however, seems their longing for "luxury" goods. Once you have been treated on a tea session or the traditional zrig (camel milk mixed with water from the well) in their khaima (a rectangular tent woven from black sheep wool and camel hair, with a bright-colored patchwork roof on the inside), it is easy to understand why — the life of these nomads is generally very basic.

|

|

Three men carrying supplies on two camels across the desert

|

On more than one occasion, a family chief offers us to slaughter one of their little goats in the hope the gesture will be honored with a generous gift: binoculars, western clothes, sunglasses, or a camera. Other times, mothers ask permission to rummage through our garbage bags in search of discarded cans from which they make toys for their many small kids.

|

|

A man standing in the desert with a goat offering.

|

In Sidatty's hometown Atar, his wife, sisters, and aunts want to show their respect and hospitality by meticulously painting geometric patterns on my feet with henna. They also surprise me with a robe and voile to match. I am invited to join the family for dinner. Seated on pillows on the floor of their guestroom, we dig with our fingers into a big bowl of couscous with one giant lamb bone on top. It is the grandmother's task to pick the bone and distribute the pieces to the various corners of the bowl so that everyone can get their fair share.

Saying Farewell

During our farewells, back at the Diama border, Sidatty does not shake hands, and looks stiffly in another direction. In Mauritania, where same-sex affection is a socially accepted phenomenon and the sight of armed soldiers walking down the street hand in hand — as a casual expression of male bonding — is nothing out of the ordinary, it is not polite to display any affection or emotion between men and women in public, nor to have direct eye contact. Instead, as a sign of respect, Sidatty touches his heart with one hand, and with the other he passes me a CD with songs of griot diva Malouma — songs which we have endlessly been listening to during our desert trek. "So you will never forget" he whispers, then abruptly turns around and disappears, not even looking back once. The tea session at the border crossing is already in full swing, and this time, the customs official and I drink to the great and unforgettable land of Mauritania before I set foot again in neighboring Senegal.

|

|

Red and orange sunset in Mauritania above the sand dunes.

|

Lies Ouwerkerk is originally from Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and currently lives in Montreal, Canada. Previously a columnist for The Sherbrooke Record, she is presently a freelance writer and photographer for various travel magazines.

|