Tribal Encounters in Remote Southern Angola

Article and photos by Lies Ouwerkerk

Senior Contributing Editor

|

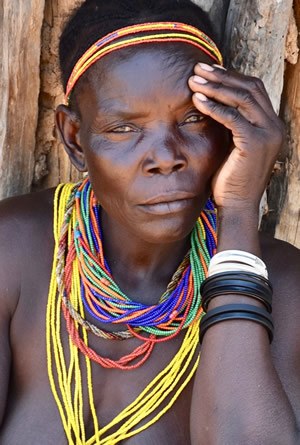

| Mucubal woman with the traditional ompota headdress in South Angola. |

In some remote areas of southern Angola, be it savanna, desert, acacia bush, forest, or dried riverbed, you can still find clusters of semi-nomadic tribal groups holding on to their traditional ways of life, completely untouched by influences from the modern world, let alone tourism.

To get there, I joined a group of 12 seasoned adventurers hailing from the UK, Australia, New Zealand, US, Germany, and Canada. Each member of the group had flown into Angola’s capital Luanda, and from there into Lubango, gateway to the southern regions and set in a lush valley surrounded by beautiful mountains.

With its run-down colonial buildings in faded pastel hues, Lubango gave us some idea of the important Portuguese settlement it once had been after hordes of immigrants from Madeira settled in the area to develop southern Angola’s interior to set up farms.

Many new constructions, bustling markets, and the modern shopping mall “Millennium” also indicated that the country is definitely redefining its identity and moving forward after centuries of Portuguese domination until as recently as 1975, followed by 27 years of civil war.

|

| Angola's capital Luanda, a city of contrasts, with a wide gap between rich and poor. |

Our guide Wilson and three other drivers with their four pick-up trucks loaded with food, water, tents, and mats, picked us up at our modern hotel in Lubango. Once well-supplied with gasoline, N’gola beer, and ice for the cooler, we left contemporary Africa behind. We started our long drive into Angola’s less trodden territory, in search of remote settlements and the traditional people who call them home.

Mugambue People

We first came upon a tiny community of Mugambue people, who seemed rather shy and overwhelmed by our sudden visit. In that same area, close to the settlement of Oncocua, we also bumped into a few Kung people, and learned that these were the last surviving bushmen — considered the region’s earliest tribe.

|

|

| Mugambue chief with child. |

Mugambue woman. |

|

| Mugambue men in front of their hut. |

Himba, Mutua, and Mucawana People in Cunene Province

The Himba are an ancient tribe of semi-nomadic herders living both in Namibia, where they have by now become a fixture on the tourist trail, and north of the Cunene River, in the remote savanna plains of southern Angola, where their presence is still hardly discovered, and has, therefore, remained most authentic.

When we reached one of their camps on an early morning, the men had already left to herd their livestock on greener pastures, but we were met by gorgeous women who happily showed us around in between taking care of their offspring, tending to their sacred ancestral fire, and milking the few cows that had remained with them.

The Himba women are famous for the red ochre paste, called oncula, made from crushed red stone mixed with animal fat. The paste is rubbed on their skin and hair to enhance their beauty. Our guide suggested that the paste also blocks hair grow on the body and protects the skin against the sun.

Their clothing consisted mainly of a handmade skirt made of calfskin, sandals cut out of old tires, and heavy jewelry around the neck. A big conch shell, considered a symbol of fertility, was dangling from the women’s traditional mud necklaces onto their bare-naked breasts.

Their hairdos, red mud-covered dreadlocks ending into black cheerleader-like pompons, were also quite remarkable. On top of their heads, they sported a sculpted three-leaf shaped “crown” called the ekori for girls, and erembe for married women, made of animal skin.

Infants had their head shaved, or had just a small crop of hair on top, young boys were wearing a single braided plait on the rear of their head, and young girls had two braided hair plaits extended forwards in front of their eyes.

We were told that although the Himba women spend hours beautifying themselves, they never wash with water, but rather cleanse their bodies in a perfumed “smoke bath,” burning aromatic herbs and resins.

|

| Himba girl in her daily attire. |

|

| Himba woman milking a cow. |

|

| Himba brothers. |

Deeper in the bush, we also visited a small settlement of wild plant-gathering Mutua (also known as Mohimba or Muhimba) people, very similar in appearance to the Himba, although shorter in stature. The Mutua are considered a lower caste by other tribes since they don’t own land or animals and seem to be less preoccupied with their looks.

The friendly and outgoing Mucawana people, who danced and sang for us, also appeared stunning with the many multi-colored beads around their foreheads, necks, ankles, arms, and waists, and iron crosses on their backs. Their hairdos, especially the front part on their forehead, were stiffened with a mixture of cow dung, animal fat, and herbs. They were adorned with a very special headdressm, called kapopo.

|

| Mucawana woman. |

|

| Mucawana girl. |

|

| A group of excited Mucawana youngsters. |

The Practice of Tooth Filing

Tooth filing is a longstanding cultural practice among the southern Angolan tribes we visited. The custom is not only found in African cultures, but also in countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia, ancient China, and Mexico.

It is commonly assumed that tooth filing was used in the past as a rite of passage to adulthood, as a means to imitate animals, or for spiritual reasons. Some anthropologists also suggest that tooth filing dates back to the time of the slave trade. Slaves used it as a way to spite or dissuade slave traders who much valued the whiteness of their teeth.

Whatever the original aim may have been, tooth filing in Angola is now mainly practiced either for aesthetic reasons or to identify an ethnic group. I regularly saw, especially in women, two front incisors filed in an inverted V shape, showing a triangular gap every time they smiled. But I also noticed people with one upper tooth or two front bottom teeth knocked out, or with teeth filed like a cow’s, possibly to suit their still widely-practiced animistic cow worship rituals.

Some tribe members also explained to us (via their kids, who had mastered some Portuguese in their “open-air school” in the bush) that when speaking with a gap in the front teeth, their words sounded so much sweeter!

|

| Filed upper teeth and extracted lower teeth. |

Mudimba, Muila, Mucabal, and Nguendelengo People in Huila and Namibe Provinces

Around the small town of Otchinjau, we met a group of Mudimba people at the local market. The women were wearing western clothes, including bras, a remnant of the time missionaries in the area tried to “educate” them. Most of the women also had scarves around their voluminous Afro hairdos, whereas the girls were wearing traditional beaded wigs indicating that although they had reached puberty, they were not yet ready for marriage.

|

| Mudimba girls with beaded wigs, called ena. |

Shifting direction, and setting course west for the coastal town of Namibe in Namibe Province, we stayed overnight in the colonial settlement of Chibia on the Huíla Plateau, where the Muila people are living. Muila women are famous for their ornate hairstyles prepared with a mixture of mud, butter, crushed tree bark, cattle dung, shells, herbs, and even dried food. Their foreheads are shaven — considered a sign of beauty — with hair divided in the back into four or six mudded dreadlocks, called nontombi.

The women were also wearing impressive, colorful necklaces made of stacked-up beads covered with mud, called vilanda for women and the thinner vikeka for girls (which they carry until marriage). Once on, the vilanda necklaces are never removed. To be able to sleep with them the women use special headrests.

|

| Muila woman with traditional necklaces and dreadlocks. |

The women of the Mucabal people, a subgroup of the larger Herrero ethnic group we met in the bush around the town of Virei, had a particularly eye-catching and unique headdress called ompota, made of a wicker frame filled with cow tails and covered with a colorful scarf. An interesting detail was the string around their breasts, the oyonduthi, which was used as a bra. Women and girls also sported iron anklets, mainly worn for adornment, but reportedly also used to protect themselves from snakebites.

|

| Iron wired anklets never come off... |

In Mucubal culture, the supernatural and ancestor worship is highly valued. Their graves are decorated with a large number of cattle horns, symbolizing the cattle owned during life, and they often wear talismans and amulets to ward off danger or misfortune.

Babies carry a carved piece of wood on their back, which is only removed once they can solidly walk, and then kept for the next.

|

| Mucubal baby boy with wooden talisman on his back. |

Finally, while camping close to the village of Garganta, a former Portuguese mining enclave, we encountered a small group of the remaining (300 to 400) Nguendelengo people in Angola, who were eager to perform mesmerizing and acrobatic dances for us.

Hunters and gatherers, the Nguendelengo are a subgroup of the Mucubal, and although the women had similar strings around their breasts, they had their own, unique bun-hairstyle.

|

| Proud Nguendelengo girls. |

|

| Nguendelengo women adhere to the same 'rope bra' fashion as the Mucubal. |

Topography Of Southern Angola

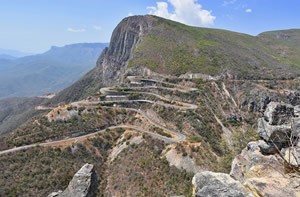

Most of the terrain we covered was savanna, grass, and woodland, with a little bit of desert (Namib Desert) in the far South, some mountains around Lubango (Tunda Vala escarpment) and the Serra de Leba Pass close to Namibe Town.

|

|

| Namibe Desert. |

The Serra de Leba Pass. |

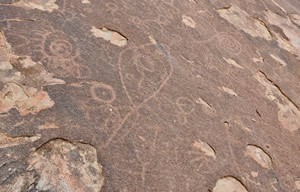

A special mention goes to the Welwitschia Mirabilis plant, endemic to the Namib desert and able to grow for at least 1000-1500 years, and the prehistoric Tchitundo-Hulo rock paintings in the middle of nowhere, west of Namibe. But what astounded me were the spectacular Curoca rock formations on which the sunrays of the early morning and late afternoon cast a magical spell. Camping amid these mysterious natural wonders was for me the icing on an already rich tribal cake.

|

|

| Prehistoric art on Tchitundo-Hulo rocks. |

The magical Curoca rock structures. |

For More Information

Portuguese is Angola’s official language

- Although Angola’s economy is one of the fastest growing in the entire world (oil, gas, and diamonds), life is expensive. Poverty is still rampant since most revenue does not end up with the Angolan people but in the pockets of a few privileged individuals or multinational corporations

- Angola is predominantly a cash society, even in the larger cities, with the kwanza as the official currency. We obtained local bank notes by changing U.S. dollars through a moneychanger arranged by our local guide, but U.S. dollars can also be changed for kwanzas at the "banco" counters of big supermarkets or in hotels. In banks there are often long lineups, and the exchange rate is not necessarily better

- Since the end of the civil war (2002), safety and security have improved drastically, although some neighborhoods in the bigger cities are best avoided due to poverty-driven robberies. The risk of international terrorism is considered low

- Landmines remain a concern in certain regions of Angola, but the three southern provinces we visited (Huíla, Cunene, and Namibe) are considered landmine-free

- Be aware that the process of obtaining a visa for Angola is slow and complicated, so an early start is recommended, as is the service of a visa agency as a go-between

|

Lies Ouwerkerk is originally from Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and currently lives in Montreal, Canada. Previously a columnist for The Sherbrooke Record, she is presently a freelance writer and photographer for various travel magazines.

|