Study Abroad and Volunteering in Chile

Learning Acceptance of New Ideas

Article and Photos by Tamara Smith

"No," I said firmly but smiling, "No." My Chilean host mother responded with complete silencio, followed by the most crushing look of disappointment as she retracted my plate full of cooked octopus and onions from the placemat before me. My stubbornness was sucking the life from the room, and in my first week of life in Concepcion,

Chile, that was not the effect I had hoped to have. In a futile attempt to smooth things over, I gently added in my broken Spanish, "I'm sorry, but I don't eat the fish with the eight legs." She gave me a look of reproach and said quietly, "Why are you such a frog in un pozo?" Baffled initially, I skimmed my Spanish/English dictionary to discover that un pozo means "a well." Shamefully, I realized that what she had meant was that I was being close-minded, that it was as if I were a tiny frog, trapped and unable to see further than the walls of my mental "well."

After that scolding, I decided against the persistent warnings of my wary stomach and reclaimed my plate. As lunch continued, I made a quiet resolution through the labored mastication of that miserably chewy, sponge-like, tentacled flesh. From then on, I knew that no matter what events awaited me in Chile, I did not want to be the frog in the well. Caution is one thing, but what is travel if not the chance to be wholly immersed in a different way of life, even if that immersion includes consuming stuff we had never even considered food before seeing it on our plates?

The good thing is that the choice to study abroad already proves that most of us are trying to jump out of our wells. We want to see what else is out there and experience it first-hand, not solely through magazines and Travel Channel specials. The unilateral worldview that plagues so many Americans is slowly broadening. We do not want to read primary sources; we want to be them.

But once that decision has been made, we are left wondering — what should we do next to prepare? The answer to that is simple — research. Find out about your new home country's foods and customs. Learn about their history and their national holidays. All of this has plenty of practical applications. Perhaps if I had known all about the unique creations that the coastal-dwelling Chileans concoct with fish, I would not have been so vague when I told my host family that I liked seafood.

After my arrival, I quickly realized that life in Chile is not much different than in the United States. People did not stop living when I arrived and have kept living since I left. Aside from a few idiosyncrasies like lighting a pilot each time I wanted to shower, throwing used toilet paper in the garbage bin aside from the toilet because of the poor plumbing system, seeing stray dogs everywhere, and the fact that everyone was speaking Spanish around me — my life proceeded as well. I still woke up every morning, went to class, learned dirty words and funny idioms from my Chilean friends, ate empanadas, and danced. We also watched Papi Rick, and other Chilean television shows with my host family. All that was necessary was a willingness to adapt and to become involved in the lives of the people around me so I could be a part of how they live.

Travel became central to the experience. Nearly every weekend, I would travel with other students from the program to different parts of Chile and neighboring Argentina. We visited fjords, glacier lakes, sleepy beach towns, lunar landscapes, and vibrant cities like Santiago, Valparaiso, Buenos Aires, and Mendoza. I stayed in Concepción other weekends and did things with my Chilean family and friends. We went to the local rodeo, had a big Sunday lunch with the extended family, and played paddleball on the beach.

The key is to be open to exploring whatever the situation, whatever the landscape. Before arriving in Chile, I never thought I would climb an active volcano, visit the bottom of the American continent, or swim in the frigid Strait of Magellan. But now, it is impossible to imagine not having done it.

|

As the program ended, I decided that I was neither satisfied with my fluency in Spanish nor my all-too-short three months of adventure. I needed more. I set up a leave of absence with my home university, checked web postings for English teaching jobs, sent resumes to multiple institutions, and waited for responses throughout the summer. As it was nearly impossible to find teaching jobs over the summer because it was vacation time, I started getting response emails and interview requests near the end. Once the employers began contacting me, it became apparent that one of the most essential pieces to selecting a workplace is to visit the site and make sure that the terms of your employment are clear. Not only was it beneficial because I could see what I might be getting into, but also because the chance of getting hired increases considerably if you are already present and knocking at potential employers' doors.

I eventually settled in Vina

del Mar, Chile, with a six-month volunteer preschool teacher position. The job provided for room and partial board but no monetary compensation. When funds began to run low, I searched for alternate sources of income. I put an advertisement for English classes in the local Sunday paper. Much to my astonishment, my phone rang constantly for the next two weeks. A simple and easy trip to the local newspaper office blessed me with steady classes for the next five months. I was even contracted to translate a love letter for a Chilean man who had become enamored with an American woman he met over his summer holidays. At first, I declined, worried that I could not translate his Spanish effectively. However, after his persistent reassurance, I gave in, realizing that the willingness to try was still the most important thing in the situation.

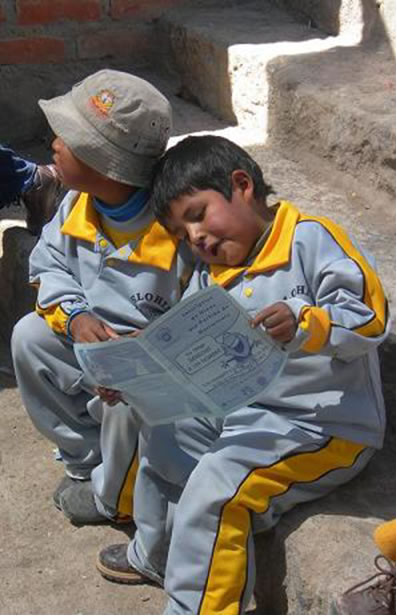

Even more astonishing was the life at the Preschool that taught me things I had never dreamed of. I taught cartwheels and Ballet, ceramics, painting, and reading and writing to Chilean kids aged 2-6 in an English immersion setting four days a week. That experience provided the realization that I had finally internalized my philosophy of avoiding the "frog in the well" syndrome. As Africa was the topic of the month in the science room, the head teacher asked me to incorporate some of its culture into my gym classes. So, after a bit of web research and some informational videos, I pumped up the volume and taught them everything I knew about Afro-Brazilian dance. While my moves were novice at best, the experience taught me that if I can get a group of 3-year-olds to shake their bodies in unison to tribal dance music, I can do just about anything.

|

When you boil it down, studying, volunteering, and working abroad is about trying different things and molding your worldview to incorporate the beliefs of others. Making funny language mistakes, eating interesting food, swimming in the Strait of Magellan, or translating Chilean love letters are part of the bargain. We were meant to adapt; the truth is that leaving home is the hardest part of it all.

Tamara Smith studied abroad

in Concepcion, Chile, at the Universidad de Concepcion through

the Education

Abroad Program (EAP) at UCDavis at UC Davis from September 7, 2006-December 9, 2006.

From December 2006 to February 2007, she traveled extensively through Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay. Tamara then returned to Chile and found work at the bilingual Preschool, One World Nursery, in Viña del Mar, Chile, as a volunteer teacher from February 2007 to July 2007. She also taught private English classes to workers at a Chilean shipping company in Valparaiso, Chile, during that time. After traveling through Bolivia and Peru from July 2007 to August 2007, Tamara returned to California on September 4, 2007.

Tamara grew up outside of Washington, D.C., and moved to the greater Sacramento, CA, area when she was 16. She will graduate in June 2008 with a bachelor's degree in Linguistics from the University of California at Davis.

|