Student to Student

A Desert Dream

Studying and Living Abroad in Cairo and Traveling in the Dunes of Egypt

By Rachel Tobias

|

|

A typical scene with camels passing by Giza in Cairo, Egypt. |

The sun has set behind the swampland of the riverbed as we float on a felucca, awaiting a glorious Nubian meal prepared for us by our crew of two men. We spent the afternoon reading, sipping hibiscus tea, and listening to the Nile lap our inner rhythms. Our first mate quietly takes a break from preparing our supper to spread his small rug out on the hull and proceed with his evening prayer — standing, kneeling, meeting his forehead to the carpet, and repeating. We will spend the night on this felucca, lulled to sleep by whispers of the Nile and campfire kisses. The warm air turns cold in the early morning, but watching the sun rise over the palm trees is worth it.

|

|

A felucca sailing down the Nile in Egypt.

|

I will break out the watercolors (a new resolution to paint once or twice a week) and let my mind wander as I try to capture the scenery on a small white page that barely does justice to a water droplet. I envision myself in a new place and land, experiencing a different culture with its ways of life and thought. Some I will agree with, some I will not. But at least I can understand "why" — which quickly is becoming my favorite word. I wonder whom I will befriend. Or who will befriend me? What will I miss most from home?

Finding My Place in Egypt: The Land of Insha'Allah

|

|

Cairo skyline beyond mosques.

Cairo skyline beyond mosques.

|

Because I had spent two years learning Arabic at the University of Southern California, intent to learn a language that could potentially connect me with the cultures and countries we have yet to make peace with, the only two options for studying abroad through my university (and receiving transfer credit) were Egypt and Jordan. The 6th-grade history buff in me who had always made me yearn to see the Great Pyramids urged me to choose the land of King Tut. And so, in August of my junior year of college, I found myself wandering the streets of Cairo.

|

|

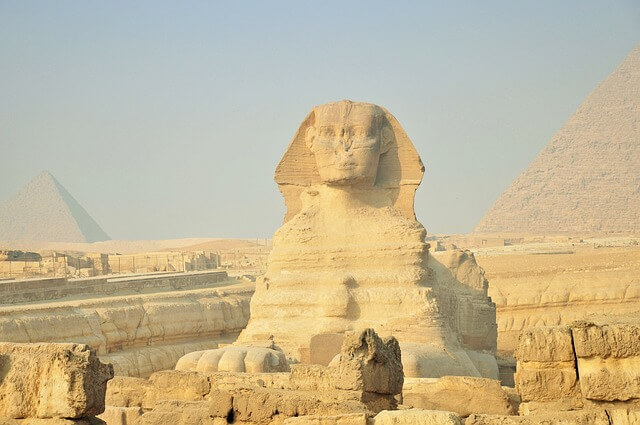

Pyramids and the Sphinx in Giza, just outside Cairo.

|

The first obstacle was finding a place to live. The American University in Cairo was about an hour from downtown, making the commute and the idea of living on campus unappealing. If attending AUC, you have the option of staying in alternative dorms in Zamalek, which is a small island on the Nile right in the heart of Cairo, still connected to the madness of the city by straddling bridges which I had to cross every day to begin my long journey to the University. This island is the hub for expatriates and diplomats; most foreign embassies and consulates are on this little patch of land.

For a first-time resident of Cairo, Zamalek is an ideal place to live. Zamalek is a lovely place: it is one of the city's higher-end places, and its spattering of embassies makes it the primary place of residence for many diplomats and expats. There are many cafes, shisha bars, food delivery bikes, and taxicabs, which beep their horns as regularly as they breathe. Good supermarkets like Seoudi Market, Alfa Market, and Metro carry some American brands of food and other products. On Halloween, I even found canned pumpkins to make pumpkin pie. Aside from having some conveniences to cater to foreigners, Zamalek has the perfect combination of Egyptian culture and language without being overwhelming or intimidating. Although it is a higher-end area, you will still be greeted each morning by families of cats gracing your doorstep, scavenging for treasures in the garbage that decorates the streets. I learned to walk on the pavement rather than the sidewalk since turning an ankle on the cracked and uneven concrete is easy, and the external air conditioners dripping onto the sidewalk are not an appealing alternative to a shower.

If you want to stay in a local area with little contact with tourists, consider Downtown or Mohandiseen. Options for those looking to avoid local areas may wish to explore Maadi, which feels almost like a U.S. suburb. Zamalek was a great place to be, although I decided to live in my apartment rather than the AUC dorms. I wanted to interact with the locals and have a life separate from AUC After all, learning Arabic would not happen in a classroom. I rented an apartment for about a third of the price I would have paid for the same apartment in Los Angeles.

Despite the very low cost of living and the quantity of foreigners living in Zamalek, it is still hard to find the same quality of life you might find at home, as you should anticipate. For example, I would constantly return to my apartment to find that we had no water or internet access. I rarely had hot water and never found a clothes dryer, even at the “dry cleaning” shops. I learned to love my starchy, air-dried wardrobe and my loose jeans. Every apartment has a bowab, or doorman, who oversees those moving in and out of the building. Few of the bowabs or landlords speak English, so trying to get anything fixed can be a struggle. “Plumbing” vocabulary was not in my Arabic dictionary. If you decide to live in an apartment, finding a building whose bowab speaks at least some English is preferable.

Even though my second bowab spoke enough English and enough Arabic to communicate effectively, I still had to learn the art of patience. Egypt is the land of Insha’allah. Insha’allah means "God willing." Everything in Egypt is "God willing." We will have water by 5 p.m. Insha’allah. I will see you tonight. Insha’allah. Is the plane leaving at 10? Insha’allah. May I please order dinner? Insha’allah. This was where I had to adapt to a slower mode of living and means of action. The fast-paced way of living that I was used to in Los Angeles was not to be part of my everyday experience in Cairo, and learning the art of patience was a process.

Life as a Woman in Cairo

While I went to Cairo to experience a new culture and way of life, part of me believed I would be an observer. However, travelers need to realize that there is no such thing as observing your surroundings. We are all active participants in the world around us, even if we are quietly sitting on the outskirts. At first, I did not believe that I would be poorly treated, even as a woman. After all, I was only an observer. How wrong I was.

I dreaded walking to the school bus every morning, a trepidation that arose from knowing I must keep my head down and wear sunglasses to avoid eye contact with any men. I always dressed conservatively, often wearing jeans and a tank top with a cardigan, never showing my legs, shoulders, or cleavage; however, it probably would not have made much of a difference if I had been naked: my blonde hair and white skin attracted attention everywhere I went. As I walked down the street, I would hear the police officers and bowabs begin to whisper and feel their stares penetrate my shirt. I was constantly angry at this situation. The other women and I could not smile and converse freely with others in the street. Angry that I had to put on a façade, and a rude one at that, to get by without any mushkelaat (problems).

For all the alarming looks and comments I received, I always felt 10 times safer in Cairo than in downtown Los Angeles at the U.S.C. I felt safe even walking alone at night in Zamalek, which I would never do near my apartment in the States. I never feared being robbed or raped, which has a lot to do both with the pride Egyptians have in themselves, as well as the high degree of religiosity that dominates all aspects of their lives.

|

|

Watermelon vendor on the outskirts of Cairo.

|

However, there appeared to be a lack of respect for women in Egypt. I taught refugees once a week in an area of Cairo called Ain Shams, about an hour and a half from my house in Zamalek. The cab ride can be expensive (less than $10, but expensive when you have adapted to the currency), so I usually take the metro home since it costs 1 Egyptian pound (less than 20 cents). Each train on the metro has a car specifically designated for women. Men are not allowed in this car, although if you are a woman, you are welcome to ride in the men’s car. I did not know about the women’s car my first time on the metro, so I hopped onto the first car I found open. The train was crowded; only men were pressed onto me like sardines. After a few minutes, I felt someone’s hand touching my butt; since it was so crowded, I assumed it was an accident and started to move to another wall of the train. I realized the man who had been grabbing me was following me as I moved around the train, his hand on my butt the whole time with the most innocent look on his face. Had this happened at the end of my residency in Cairo, he may have received a good punch in the face and some rude Arabic words. Nevertheless, since I was new to the city and unsure of my boundaries, I remained quiet, and his hand remained on my rear.

From then on I rode in the women’s car.

On The Road in Cairo

Imagine a freeway in the U.S., which has four, maybe five lanes for traffic. Most people use their blinkers to change lanes, and people wear seatbelts. Now imagine a freeway in Cairo. There are still four lanes of traffic, with seven to eight rows of cars wedged in together. Cars cross three lanes simultaneously, swerving left and right as they please at incredible speed, never thinking to use a blinker. Horns replace breathing on Cairo roads. Donkey carts, buses, and taxis populate the road at the same time.

|

|

A flatbed truck carrying a camel. Photo by Rachel Tobias. |

There are different types of taxis in Cairo. The black taxis are cheaper but have no meters and no seatbelts. Cairenes do not believe it is possible to die if sitting in the backseat of a vehicle and, therefore, cut out the seatbelts for the sake of comfort. Yellow or white taxis have a meter and are a safer option for those who have not yet mastered the art of negotiating the price of a trip. Taxis are a great way to practice your Arabic. Chances are that cab drivers will only want to talk about former President Obama, reflecting the incredible change in Americans' perception of the Middle East.

Embracing Egyptian Culture

|

|

Some of the many hieroglyphics covering the Luxor temple in Egypt. |

Ramadan happened to fall during my first month in Egypt. Ramadan is the month of fasting, during which practicing Muslims should not eat, drink, or smoke from sunrise to sunset. Alcohol, sex, and drugs are forbidden for the month. For that month, there were limited signs of life during the daylight hours: workdays were shortened, and people slept during the day, waking up at 6:30 p.m. for iftar (breakfast). A typical Ramadan weekday for me in Egypt went something like this:

5:30 a.m.: Wake up for school to catch the 7 a.m. bus to the American University in Cairo with my three other American roommates. Take a cold shower (since we still have not had the privilege of hot water. Look at the bananas on the counter and resist the urge.

6:50 a.m.: Walk to the bus stop with 50 other sleepy American students. Pass the bowab on the way out of my building’s elevator. Sabbah al-haier. Good morning.

7:00 a.m.: Ride the bus about an hour to campus, during which everyone tries to get a few extra bumpy minutes of sleep.

8:30 a.m.: Modern Standard Arabic (fus-ha) with my professor Neshwa. He is very strict. I realized that I should have finished my homework instead of watching the Egypt-Algeria football match the previous night.

9:45 a.m.: Walk to my next class, trying to avoid eye contact with some more judgmental Egyptian students. The students at AUC are typically children of the Egyptian elite and are not necessarily academically motivated. More pressing to them is their wardrobe. God forbid I wear Levis instead of designer jeans – I get the “look-up-then-look-down” from every Egyptian girl. The girls are glittering in Prada sunglasses and Coach sneakers; they do not carry books or notebooks to school…once in a while, they carry a tiny notepad, which I suppose could hold maybe a quarter of a century’s worth of notes in history class.

10:00 a.m.: Egyptian Colloquial (ameeya) with Professor Neshwa. Colloquial language is necessary to communicate with Egyptians. While they will probably understand your formal Arabic, they will laugh at you: imagine one of your classmates speaking like Shakespeare.

11:30 a.m.: I walk to my next class. It is desperately hot, and I really wish that I could drink some water.

11:45 a.m.-3:30 p.m.: My other classes, depending on the day, include Intro to Development, Contemporary Political Islam, and the Rise to Power of Islamic Movements. Learning about Development and Islam from a completely non-American perspective is fascinating.

4:00 p.m.: Board the bus to return to Zamalek. Counting down the minutes to iftar, or “breakfast,” when I will be permitted to have my first meal of the day.

5:20 p.m.: I return to the apartment after walking past a quiet neighborhood. At the same time, everyone twiddles their thumbs until they can eat again. I nap, so I do not think about how much water I crave.

6:30 p.m.: IFTAR! Al-hamdul Allah! Thank God. Eat iftar either with friends or have something delivered. Everything can be delivered in Egypt. Any bizarre craving you might have could indeed be satiated by a deliveryman. The most popular restaurants that allow you to order online are at www.otlob.com. I go to iftar at my Egyptian friend’s family’s house. It is mouthwatering, with piles and dishes being served at a furious pace I can barely keep up with. There is koshary (rice, lentils, noodles, and a spicy sauce), sambousek (fried cheese), kebab, kofta, falafel, hummus, fool (very similar to Mexican bean dip), yogurt, and mint dip. And then there is the fresh juice, which is one of the most delicious treats one can find in Egypt. They have juice in every flavor, although I prefer bateekh (watermelon) or ananaas (pineapple).

7:15 p.m.: Food overload. Turn on the T.V. to take my mind off how full I am. Pick one of our four English channels, and I am stuck watching “A Walk to Remember.” Mandy Moore and Shane West are about to kiss. But wait, the kiss never happens. Kissing, sex, nudity, or excessive touching is not allowed on Egyptian television. The movie goes into a commercial. It is an anti-drug ad. Another commercial comes on. It is a pro-prayer ad. One of the most interesting changes here has been the lack of separation between church and state. In the U.S., many of us are used to being able to say and do whatever we want, whenever we want. People who have religious beliefs can make their own choices. In Egypt, the society and the government make your choices for you.

9:30 p.m.: Get dressed and meet friends for shiisha, the social pastime of almost everyone in Egypt.

12:00 a.m.: Order sohoor (dinner/lunch). Usually, I would like something light since I still cannot justify eating a full meal at midnight. Sit with my Egyptian friends and share stories. My friends speak primarily in Arabic, translating for me now and again, forcing me to practice speaking to them in Arabic and not English.

A Desert Dream

|

|

Camels crossing the desert at sunset.

|

One weekend, we decided to break from the city madness and escape to Siwa Oasis, a 7-hour drive from Cairo. We spent our days sandboarding down giant sand dunes, pruning ourselves in bubbling hot springs, and absorbing the magic of Bedouin camps. Sitting on a sand dune one evening, I watched the sun burn orange and purple into the dunes as it retired for the night. I looked across the hundreds of miles of desert surrounding me, knowing this was a perfect moment.

I do not know if it was the sand, wind, or water, but Siwa had seeped inside me, infected my brain with its witchery, and captured my heart. Memories of the past six months began to set with the sun as I recalled them. I was lucky to have had such wonderful Egyptian friends. I had the privilege to shake hands with Egypt in a way that I never would have without being able to see things through the eyes and hearts of locals. I faced many frustrating and weary challenges, especially as a woman, but the challenge was the goal of the experience. I became a “local” resident in my own way, participating rather than observing and embracing the joys and frustrations of living in this captivating land.

Rachel Tobias is a junior at the University of Southern California, majoring in International Relations and minoring in Entrepreneurship. Born and raised in Los Angeles, California, Rachel has had the privilege of traveling to many different regions of the world. She is fluent in Spanish and developing proficiency in Arabic. Once she graduates from college, she is interested in working in international development in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East.

|