Transitions Abroad Thirty Years On

The magazine

founder and publisher offers his perspective on how travel

and travelers have changed over the past three decades

by Clay

Hubbs. Ph.D.

|

|

Founding publisher and editor

Clay Hubbs enjoying some local wine at the pergola cafe

at his adopted hilltop village in Tuscany.

|

In 1977 I introduced the first issue

of Transitions Abroad magazine by describing

our intended readers as “non-touring travelers” for

whom learning — about the world and about themselves — was

the principal reason for going abroad.

In the same issue Gary Langer, then

a student at the Univ. of New Hampshire, wrote about his

stay at the Jerusalem guesthouse of an eccentric Armenian.

Only travelers stay at Mr. A’s, wrote Langer; tourists

do not.

“The distinction is simple:

Tourists are those who bring their homes with them wherever

they go and apply them to whatever they see. . . . Travelers

left home at home at home, bringing only themselves and

a desire to see and hear and feel and take in and grow

and learn.”

Since that time the traveler/tourist

distinction has become something of a cliché,

one that taken literally makes no sense. Outside our

own country we are all seen as tourists; even we use

the word tourist to describe the “other guy.” What

distinguishes one tourist from another is how we travel,

not where or even why. What distinguishes Transitions

Abroad readers from the other guy is a desire to

learn from our hosts, openness to change, and a desire

to share life's pleasures.

The purpose of the magazine

was never to tell readers how to behave abroad but rather

to provide the detailed information they need to enable

them to meet people of other countries, to speak their

language, to immerse themselves in their culture, and

thereby to “transition” to a new level of

understanding and appreciation of our common humanity.

The title, “Transitions,” was meant to suggest

the changes in our perspective that result when we get

away from the tour bus and beyond the postcards.

London's Calling

A few weeks ago the phone rang in the

middle of the night. It was the BBC calling from

London. They wanted to interview me about a story that was

making the rounds on the Internet. Big U.S. companies, fearing

anti-U.S. backlash, were teaming up to offer advice on how

to improve the behavior of business travelers overseas.

At first I didn’t see the connection

between Transitions Abroad and the behavior of

business travelers. Then I saw that this was an extension

of the traveler/tourist distinction.

“We are broadly seen throughout

the world as an arrogant people, totally self-absorbed and

loud,” said Keith Reinhard, chairman emeritus of DDB

Worldwide Inc., who heads up the effort to combat anti-U.S.

sentiment abroad through a group called Business for Diplomatic

Action, Inc.

The producer of the BBC radio talk

show wanted me to talk about the “Ugly American” and

how the behavior and the image of Americans abroad has changed

over the past decades.

The "Ugly

American" Myth and Conundrum

I’ve traveled abroad at least

once a year since the 1950s and lived abroad for varying

lengths of time. From what I’ve seen I’m not

convinced that Americans’ behavior is any worse than

that of other nationalities. But because of our physical

isolation and poor public education we perhaps are more

naïve than the average European traveler. And in our

naiveté we may sometimes draw attention to ourselves.

The BBC reporter gave me a few hours

to think about my response before calling back. During that

time I reflected on how travel and travelers have changed

over the past half-century.

In the decade or so after the end of

World War II I saw the worst examples of “Ugly American” behavior.

America had won the war. Those Americans who stayed behind

to help in the rebuilding of a devastated European continent

often did not seem ready to give their hosts credit for

their help in bringing the war to an end and the price they

had paid in the process. Americans often behaved like conquering

heroes. “How much is that in real money?!” is

just one example of the arrogant and ignorant behavior I

witnessed.

The sixties revolution brought hoards

of young people (including me and my wife in 1963) on pilgrimages

to the East. We made our trip in a VW bus across North Africa

and the Middle East to India, following the path of Alexander

the Great. Rather than being arrogant, our generation was

awed by all the “culture” we found in Europe

and beyond. As my wife and I went deeper into the Arab world

we gradually realized how limited and distorted by cultural

bias our perception of the world had been. From a guard

at the abandoned site of Persepolis we learned that our

hero Alexander was remembered locally as a destroyer of

a great empire.

|

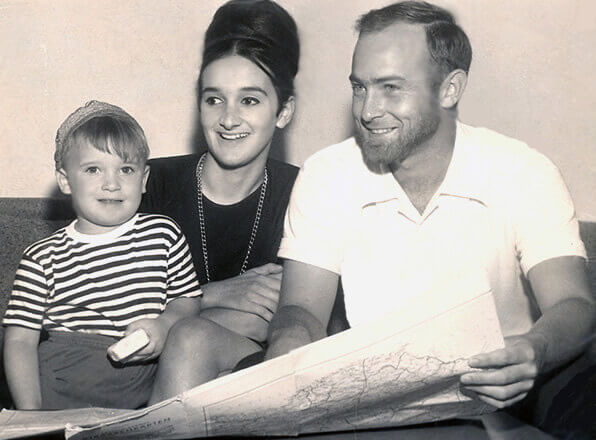

With his family in 1964 after

returning from years of adventures in

England, North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.

|

The ‘70s and ‘80s were

marked by a boom in mass tourism and packaged tours. In

the mid-‘70s my family and I took an extended sabbatical

in the South of France. Every week I went to Monte Carlo

for a French lesson (while my already-fluent family ate

pastries underneath the window of my language lab).

After my classes we walked over to

the famous hotel-casino and got to know some of guests.

It turned out that many of them were there for a 1-week

gambling vacation. They were picked up at the Nice airport

and bussed to the hotel and at the end of the week bussed

back. Many never left the hotel, yet they boasted that they

had been abroad.

How to Best Disseminate Information?

I was convinced that the major reason

that so many people were traveling in groups was the lack

of easily available information on how to travel on their

own. During that same year we learned how hard it was to

find information on schools for our children, and, when

we decided we wanted to extend our stay by finding jobs,

how difficult it was to find information on overseas employment.

That was when I decided to start Transitions

Abroad. Our first task was to collect information

and evaluate it. What were the best resources (information

sources) for work, study, travel, and living abroad?

To do this I contacted the top authorities in the four

fields and asked them for their selections. This was

an ongoing task; we updated — and, with the help

of our contributing editors, continue to update — the

lists each year.

The next job was to make this information

available to as many people as possible who could use it.

Before the advent of the Internet this — like the compiling

and updating of the “Best of” lists — was

not easy. But largely by word of mouth more and more people

found us. And once we had a substantial readership, we had

our major source of contributors — our own subscribers.

Soon a large portion of each issue was devoted to “participant reports,” first-hand accounts of how individual readers

succeeded in finding the work, study, travel, or living

programs best suited to their needs — or, more frequently,

used the magazine’s resources to create them themselves.

To return to the traveler/tourist dichotomy:

the one thing that distinguishes Transitions travelers from

ordinary tourists is that they travel for a purpose other

than simply diversion or escape.

The Impact of 9/11

And to return to the question of how

the behavior and the perception of Americans abroad has

changed in recent years, it’s clear that the ugly

American label only reappeared after our country’s

invasion and occupation of Iraq. After 9/11 we saw a worldwide

expression of sympathy and support (“We are all Americans

now,” proclaimed France’s leading daily.). Americans

already abroad and students who flocked after them were

treated warmly.

But now all that has changed. For a

time anti-Americanism focused on government policies and

the world held Americans in higher esteem than America,

according to America

Against the World: How We Are Different and Why We Are Disliked (Andrew

Kohut and Bruce Stokes, Times Books, 2006). But now foreigners

are “increasingly equating the U.S. people and the

U.S. government.” According to polls conducted by

Kohut and Stokes, “the American people, as opposed

to some of their leaders, seek no converts to their ideology”;

we are not cultural imperialists. What we are guilty of,

write Kohut and Stokes, is indifference to global issues.

In general, Americans have “an inattentive self-centeredness

unmindful of their country’s deepening linkages with

other countries.”

Kohut’s and Stones’ assessment

is a dark one — one that I believe the readers of Transitions

Abroad do not share. Time and time again in our pages

readers describe not only the changes in their perception

of the world as a result of their travel but ways they have

become involved in making positive contributions to the

situations in which they found themselves — either through

volunteer work or direct financial contributions.

A Vision for a Positive Future

Kohut and Stokes measured the opinion

of Americans on the part of the rest of the world and the

attentiveness of Americans toward other countries at what

must be a low point for both. If their polls could project

into the future the picture would surely be quite different.

In the first place, that reservoir of good will toward Americans

(as opposed to our present government) is not gone. On this

side, a new generation of young people rushed to sign up

for study abroad as a result of 9/11 and the subsequent “war

on terror.” Even larger numbers are traveling on their

own. In the next 30 years I predict a remarkable transformation

in ordinary Americans’ engagement with the rest of

the world, partly in reaction to the present (2006) government’s

arrogance and willed ignorance.

Transitions Abroad will

continue to point the way toward positive change through

travel — not just change in individual perceptions

but putting what has been learned to use to make the

world a better place for all of us.

Dr.

Clay A. Hubbs was Transitions Abroad's

original founder, editor, and publisher.

|