Honoring Tradition in Oaxaca, Mexico at the Day of the Dead

Visitors Find Meaning in Día de los Muertos

By Jim

Kane

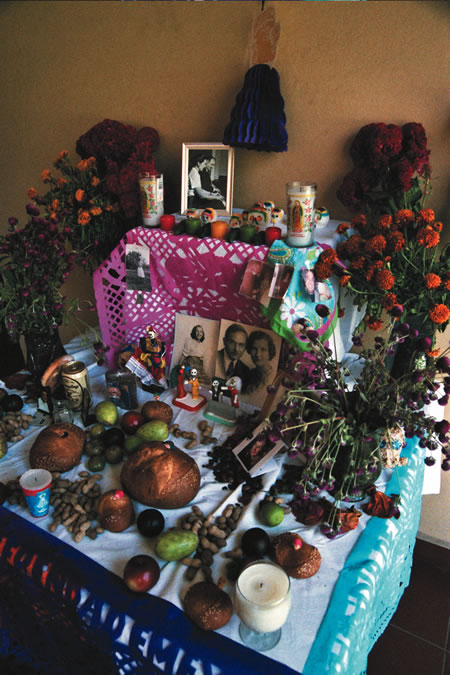

Culture Xplorers' Group Altar in Oaxaca, Mexico. Photo by Jim Kane.

Our altar was simply beautiful. It was small and not particularly dramatic, yet it exuded a warmth and charm that radiated from its every loving detail. Nearly a dozen family photographs were carefully arranged among a colorful array of offerings, all meant as a celebratory feast for the deceased family members who would return over the following two days to be — at least in spirit — with their living relatives.

Several varieties of fruits shared the table with peanuts, marigolds, candles, colorful cut paper known as "papel picado," skulls made of sugar, and the semi-sweet "pan de muertos," which is made only at this time of year.

The real character of the altar came from the personal items: the figurine in honor of a teenage niece, sand in a jar to remember a husband's homeland, a pretzel propped against a beer in memory of a loved one's favorite snack.

Several feet away, those who had decorated the altar together sipped frothy hot chocolate and shared a loaf of pan de muertos. The tiled patio rang with conversation, punctuated by smiles, laughter, and quiet reflection. The celebration would continue over the following two days with a visit to the cemetery and a feast of mole and mescal with friends and neighbors.

Angela, the flower vendor in Oaxaca who sold the author

marigolds for his group's altar.

Photo by Jim Kane.

In most respects, this was the epitome of the wonderful way Oaxacan families honor their dead every fall, making it one of the most unique and spiritual celebrations in the world.

However, there was one notable exception. None of us are Mexican; we are seven Americans and two Austrians who had all come to Oaxaca to participate in this most beloved of Mexican traditions.

The idea of joining the celebration and immersing ourselves in the local culture was the most important common thread that bound our diverse group together, from the 23-year-old tattooed and pierced punk rocker on his first trip outside the U.S. to the 68-year-old globetrotting grandmother.

As travelers we long for immersing, personal experiences on our journeys. After 16 years of travel and living abroad, I've come to value the idea of actively participating in local culture to deepen the travel experience, as long as local mores are always respected.

But as the trip leader I wondered what Oaxacans would think of us foreigners crossing the line from spectators to participants?

Long before initiating this trip, I decided to ask people from Oaxaca what they thought about us joining their Día de los Muertos celebration. My Oaxacan friend Lucero Topete, formerly the director of Oaxaca State's INAH, which is the National Institute of Anthropology and History, assured me that making our own offering, while remaining respectful of local tradition, was a terrific idea.

It was much better, in her opinion, than following the well-intentioned foreigners who bring flowers to the cemeteries to offer local families during their candlelight vigils. In fact, she insisted, she would dedicate a space for our altar on her land, not far from her own family's altar.

During our time in Oaxaca I continued to survey local opinion. "Participating is much better than observing," said Angela, a flower vendor from whom we bought many of our marigolds.

It was difficult to find a contradictory opinion on the subject as we walked the market, purchasing items for our offering. Matt, the youngest of the group, made grinning bulbous finger puppets of small sugar skulls that later would find a home on our altar. Gerlinde and Eda flipped through papel picado with themes of dancing skeletons found in stacks every color of the rainbow. Others bought Mayordomo-brand chocolate, which we used for our steamy, frothy drinks.

Later that same night, while in the cemetery of Xoxocotlan, I talked with Miguel Angel. For 38 years he has visited, I was told, not just on Día de los Muertos, but once a month, even though his village is one and a half hours away. "There used to be no transport here, so I'd walk or come by donkey. Now..." he waved his hand dismissively and made a whistle, "there are buses everywhere you look." He seemed exasperated by the rapid pace of change Oaxaca has seen in recent decades.

Miguel Angel, who has been coming to the Xoxocotlan cemetery

for the past 38 years.

Photo by Ben Goodman.

The more we talked the more animated Miguel became, commenting on the changes that have occurred since he was a younger man, observing others in the cemetery, and asking where we were from. This seemed like an appropriate segue to describe why we were here.

His response came simply and quickly as he reached out to shake my hand: "Thank you for honoring our traditions," he said.

"No, thank you," I said, "for welcoming us and giving us the opportunity to participate in your splendid celebration of the cycle of life and death."

JIM KANE has written

frequently for Transitions Abroad on travel with a community-based

emphasis. He is the founder and CEO of award-winning Culture

Xplorers, a recognized leader in sustainable travel.

|