Travels through Libya

Ancient Wonders

Article and photo by Victor Paul Borg

The plant called felesles lured me by its radiance and fragrance, like an irresistible sorceress tricking a man into a trap. Its purple flowers were the brightest, its leaves the most vital, and its entire body among the most conspicuous of all bushes that thrive in the central Sahara. In this place, rainfall is nonexistent, dew is imperceptible, and the closest water lies 400 meters underground. Only the White Crowned Wheatear, a black and white plumage bird, matches the felesles’ visibility. Now I rolled the leaves of the felesles covered with soft hair between my fingers and then raised my fingers to my mouth…

“Stop!” cried Mohamed Suleiman, running towards me. “Don’t put your fingers in your mouth. If you do, it would be like ingesting the most powerful cocktail imaginable — then you would tear off your clothes and run in the desert like a madman.”

Mohamed added that shepherds have to be careful that their sheep don’t eat felesles — it doesn't affect the sheep, but it would affect people who drink the milk.

It sounded poetic: drinking milk and getting a trip. But I didn’t need a hallucinogen to fire my imagination at Jebel Acacus, a vast range of mountains in Libya’s southwest corner. The landscape is surreal enough: vast valleys cutting through ranges of rotund brownish mountains, waves and humps of bright-orange sand dunes, pinnacles of black rocks, plateaus of pale sand and broken rocks, massive rocky arches and bulging ridges, and spine-covered acacia trees growing gnarled and crooked, uglier as they aged. And then there is the profuse rock art in under hangs and caves — depictions of savannah animals, hunting scenes, rituals, battles, and hunters and herders — a lost world that existed between 10,000 and 5,000 years ago when the Sahara Desert had forests of juniper and a savannah home to elephants. Now that the transformation is complete, the desolation is haunting, and the only thing that stirs is the faint hum of the wind. Jebel Acacus is a hallucination.

Driving through that fantasy landscape, we covered 380 kilometers in three days. I traveled in the lead jeep with the Libyan staff. I joined the tour as a Libyan and Tunisian tour operator guest, leading two German couples who followed us in the second jeep. I managed to get into this arrangement on the basis that I spoke Arabic — although I was still paying for the service — and this worked better for me, as I could be in Libya with Libyans. Besides, the anecdotes of Mohamed, our driver, about desert life and travelers were comical and informative.

“They think riding camels is fun,” Mohamed chuckled when we passed a group of tourists with blustered and grimaced faces leading their camels on foot. “Well, the first day is fun; the second day they can hardly withstand the soreness in their buttocks; and by the third day they are forced to walk and lead the camels. Camels love foreigners, because only with foreigners can they have it so easy.”

I could imagine the tourists’ excruciations by my relative discomfort; it was hot and rattly, dust stung my eyes and choked my nostrils, and the dryness cracked my lips. But I was content. I was in good company. Libya was better than I had imagined — and it wasn’t near as dangerous as everyone had warned me. Before my visit, exhortations came from everywhere — the conclusion in the West is that Libya is a dangerous place and that Libyans are intolerant and untrustworthy. Libyans hate Westerners, everyone told me, and they know how to use knives, too.

As an experienced traveler, I didn’t want to believe that nonsense. But still, all the appeals filled me with apprehension before I arrived, partly because the country, from the outside, is mired in uncertainties. Libya has an aura of enigma, forbiddance, and unpredictability. Less than half a million foreigners visit annually (one-fifth of them on cruises, and perhaps another fifth are business travelers), and that’s minuscule considering the country’s size — it’s half the size of India or three times the size of Thailand. It’s also a tiny number considering the heavy-weight attractions: the otherworldly desert landscapes, great ancient towns built by the Berbers, and some of the most outstanding Greek and Roman ruins in the world. The problem is that Libya remains shrouded in doubt and uncertainty: information is scarce, there is a lingering perception that it’s a dangerous place, and tourist infrastructure is undeveloped (there are only ATMs in main coastal towns, for example).

The absence of information led me to overpack. Since ATMs are only in the main coastal cities — and sometimes they don’t work, they’re unreliable — I was justly paranoid about carrying cash for an entire month. And how much money did I exactly need for a month? I wasn’t sure — there wasn’t enough information to accurately assess. What if someone mugged me? Then how would I get cash afterward? And is Al Qaida in Africa a threat in Libya? What about the illegal immigrants from sub-Saharan countries? What’s their impact on the danger scale in Libya?

Then, I arrived in Tripoli in the evening. The following day, I had the first view of the city from my high hotel room: a vista that revealed haphazard outgrowths of flat-roofed buildings in grey or white or green, interspersed by white gleaming minarets of mosques. The decay is more pronounced at street level; the crumbly Italianate and Ottoman architecture made the architectural heritage seem preciously rare. I walked past busy restaurants, new shops cluttered with electronic wizardry and propitious clothes, and men smoking sheeshas and sipping thick brews of green tea in outdoor cafes. I dawdled in the Green Square, studying the people — couples courting tentatively, young men hanging out, groups of young women with picnics unfolding in front of them. The chaos and the bustle were benign; no touts ever pestered me, no taxi driver overcharged me, and people everywhere greeted me with genuine friendliness. My anxieties began to dispel after two days in Tripoli.

But why hadn’t the number of tourists grown as fast as expected when the country emerged from the shadow of international ostracism and opened itself to tourism and investment a few years ago? I put these questions to Salvinu Farrell, manager of the Corinthia Bab Africa, Libya’s only five-star hotel that’s been a landmark in Tripoli since it opened in 2003. “At present tourism is based almost wholly on desert travel and archeology,” he said. “And that’s a niche market — can you imagine, for example, a family with children traveling in the harsh desert conditions? You can’t have mass tourism in the desert, where the season is also short. Increasing the numbers entails the development of coastal tourism; this will lure tourists who spend most of their time at the beaches, and then take a short tour of the desert and archeological sites. It’s the model that is successful in neighboring countries.”

“Another reason is the visa regime,” Farrell added. With the present visa restrictions, it's impossible for tourism to grow on a grander scale as we see in neighboring countries.” He’s talking about the mandatory requirement of taking a guide or traveling in a tour group. It makes the country artificially expensive — a discouragement to young travelers — and reinforces the perception that Libya is a dangerous place.

Another thing that makes the country seem dangerous is the requirement for tour groups to have an armed police officer travel with them. I went to the tourism authority to find out more about this. “The Sahara is a wild, uncontrolled place, and many problems might arise — people might get lost, there could be crime by non-Libyans, there are fierce sand-storms, vehicles might break down, and so on,” told me, Ahmed Basher, an information officer. There are other complications: few Libyans speak English, all street signs are in Arabic, and the security agencies’ tenuous control in the desert (the ubiquity of checkpoints notwithstanding) makes them touchy about foreigners wandering about in an unreconstructed manner (at checkpoints we had to supply our day-by-day travel itinerary in the desert). “The government cannot control the Sahara,” Basher pointed out, “so a guide and a tourist police are needed for the tourists’ own safety and protection.”

If anything, all this talk about the proverbial Wild West made me all the more eager to get to the desert despite my tinge of anxiety. We set off to the desert a few days later. I was traveling in the lead car with Mouldi, the Germans’ guide, and Hassan, the Libyan driver and facilitator. The Germans tailed us in their private campervans, and we were driving to Ghadamis, 600 kilometers southwest of Tripoli. We passed flat, rocky terrain, rising to stony mountains at Jebel Nafusa, the Berber heartland, and, although we were still at the desert’s fringes, I began to appreciate the scale and bleakness of the Sahara.

Ghadamis, a Berber town about 600 years old, is known, in tourist hyperbole, as ‘The Jewel of the Desert’ — and it certainly rings true. The city was designed for three purposes: to peaceably accommodate seven tribes of Berbers (divided into seven sections that intersect in a central square), to keep the temperature down in the summer heat crush, and to carefully manage the non-renewable underground water. It’s thriving on all three counts; its covered alleyways and densely intermeshed houses keep the town cool, and water management follows a strict and ingenious allocation system. It was once a major stop in the caravan route across the Sahara, but now it’s partly abandoned. Its former 6,000 inhabitants now live in two-storey houses in the new town and then move back into the old town in the summers when the old town — unlike the air-conditioners in modern buildings — offers a reprieve from the 50-degree Celsius heat.

Exploring the old town, stumbling in the darkness of the covered alleyways, I felt giddy, as if intruding in a secret place. The walls are dense with artistic reliefs, and at the back of the town, I found high-walled gardens of henna trees and date palms inhabited by a cacophony of bird life — turtle doves, hoopoes, green finches, redstarts, and the ubiquitous white-crowned wheaters. It’s a great spot, and I imagined a town primed for tourism — its romantic white gypsum houses converted into boutique hotels, restaurants, and cafes. But these are futuristic concepts in Libya, and the single café in the entire town was empty. So I joined the Germans for a meal in a family home, squatting in the living room, enjoying the mint-infused beef soup followed by a delectable couscous. The living room had a surreal orgy of décor — reddish geometric friezes, palm-trunk doors, colorful checkerboard carpets, and wall hangings — and I asked Hassan, a native of Ghadamis if it was done up for the tourists.

“It’s traditional design,” he replied. “All the old houses are designed like this.”

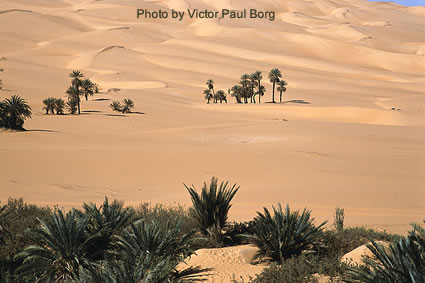

The colors outdoors were equally inspiring, perfectly fusing at sunset: the sky becoming a bleeding blue, the orange glow of the last sun seeping throughout the horizon, and matching, in a slight tonal change, the orange-brown of the earth. But were where the quintessential mountains of sand I had seen in postcards? We reached them two days later, more than 1,000km southeast, and I went running among the sand dunes, quickly exhausting myself and cursing the sand that got everywhere — in my shoes, in my bag, in my mouth, in my underwear. So I returned to the resort where we stayed, at the edge of the sand dunes in Wadi Al Hayat. I waited until the next morning when we spent a day roving in jeeps among the dunes of the Ubari Sand Sea. It’s one of Libya’s highlights, the jeeps squiggling in the endless sand and stopping at half a dozen lakes forming in the deepest valleys that dip below the water table.

By now, we were in the heart of the desert; Wadi Al Hayat, which means Valley of Life, was a massive oasis. The valley, which is 200km long and 30km wide at its widest point, is hemmed in by black-purple mountains on the south and the sand sea on the north. It’s dotted with farms, villages, and groves of date palms and inhabited by 75,000 people. The valley has been settled ever since rainfall ceased, and the scattered hunter-herdsmen migrated to the valley as the Sahara dried up. That’s when the Garamantes civilization arose; by 1,000 B.C., the Garamantes had mastered agricultural production, and they prospered and dominated an area larger than the U.K. for more than a thousand years — the Romans never managed to conquer them.

But only now, after many years of archeological excavations, is the Garamantes' extent, power, and sophistication coming to light. The Garamantes’ irrigation system, known as the foggara, is an engineering feat: it consists of 600 tunnels (with a combined length of 1,000 kilometers) interspersed with 100,000 shafts of up to 40 meters deep (from which water was hoisted up) that channeled water from the high water table at the base of the escarpments to the cusp of the valley. The former Garamantes’ capital, Garama, is now an evocative tourist sight.

David Mattingly, the British leader of the archeological research team, has hailed the Garamantes as ‘the first Libyan state’. “The archeological evidence we have now shows the Garamantes as skillful agriculturists, and practitioners of advanced technologies such as pottery-making, metallurgy, glass-making, salt-refining, and producers of semi-precious stones,” he told me. “Their society was complex, hierarchical, and well-organized; they even had a written script.”

After many years of digging through the ten layers of the old town of Garama, David’s team started exploring tombs. “After one season,” David elaborated, “we have found preserved textiles, leather, fragments of quite elaborate sewn or plaited leatherwork and much else—what we are retrieving will be the largest collection of ancient textiles from the Sahara outside Egypt and Sudan. And these finds are going to transform our knowledge of what the Garamantes looked like.”

So — another Saharan civilization suddenly bubbles to the surface. Libya has no shortage of great civilizations in its long history, and the most impressive ruins of all are those left by the Romans. After touring Wadi Al Hayat and Jebel Acacus, we drove back to the coast to see Leptis Magna, the most significant Roman ruin outside Rome. In its heyday, Laptis Magna was a major Roman city of 100,000 inhabitants. For its construction, marble was shipped from Italy. Stone was hauled from Egypt, and what’s left now easily evokes its former grandeur — particularly the massive gateway, the amphitheater bristling with columns, and the public square with its fine reliefs. It was, for us, the culmination of our 4,000-kilometer-long road trip.

And the danger? I had forgotten about the threat and only felt a whiff of fear once. That was at a small town deep in the desert, one of the first stops for immigrants from Niger and Chad. I was out late by myself, and then I had to walk back to the guesthouse on the outskirts of town. On the way, I passed dinghy restaurants where illegal immigrants loitered outside, hoping to find some leftover grub. These immigrants — whom Libyans detest as petty criminals — cross the desert on foot in quest of a single dream: a cozy life in Europe. Many don’t make it across the desert; the ones that do arrive in Libya are impoverished; the ones I passed outside the restaurants had eyes that were wild and hungry. These people have nothing and nothing to lose either — that realization chilled me, and I quickened my pace in the dark, listening out for any movements behind me.

But no one followed me, and now, back in Tripoli by myself, I felt confident and satisfied. I mingled with people in the lobby of my hotel; it was full of Tunisians who visited Tripoli for cheaper shopping and the occasional tourists. At the lobby, I met Ali, an energetic tour guide, who took me to dinner. I met Fahalla of Wahat Umm Algouzlan Tours, who also took me for dinner. Fathalla talked about two pieces of rock art he had seen in the remote Tasili Mountains: “One shows a man from the side wearing what looks like a space mask on his head and it has an aerial on the top, and the other shows the backside of a person and, in front, a planet. There is an inscription near that says, 'Beware of fire and steel.'”

It was as if he was talking about a different planet, a place that exists in fantasy. But Libya is like that, and I was reminded of this again on my last day, spent in the company of a pensioner in the Medina. He liked chatting to passing tourists; he was courteous and appreciative of people visiting his country. At one point, a European couple asked him where they could find an obscure musical instrument they were seeking. He said: “I know someone who normally sells it, but at present it’s out of stock. If you give me your address, I will buy it and send it to you.” He didn’t ask for money, only their address. The tourists smiled and declined; maybe they didn’t believe him, given his rare generosity. But he meant it, and he would have kept his word, as in Libya, over and over again. I got the impression that we are treated less as passing visitors and more as special guests. This is the nature of the country, a place that seems to exist in the imagination. Then you visit, and you realize that, despite its many imperfections, reality surpasses the imagination.

Victor Paul Borg is a writer whose work can be seen at www.victorborg.com.

|