The Death of the Red Devils

The Culture of the Diablo Rojos of Panama City

Article and photos by Darrin Duford

|

| Diablo Rojo. Calle 50, Panama City. |

I could hear one growling from blocks away. I was peering down Via España, one of Panama City’s choked-up arteries, when I reflected on how I had always likened the belabored sputtering noise to a dinosaur with a sore throat. That morning, the image would prove grimly appropriate.

Then the vehicle’s day-glow colors arrived. FAST AND FURIOUS read the script lettering above its headlights. A collection of grinning faces adorned its bumper. On the front of one rearview mirror, I found Sylvester the cat; Tweety was safe on the other. The vehicle was a diablo rojo, one of the city’s public buses, which had just stopped to collect passengers for a quarter apiece.

The diablos rojos, literally red devils, have been counterbalancing the drab concrete of the city for over four decades with their artwork-plastered bodies and obnoxious outlines of lights. Having served out their first lives as American school buses, the vehicles were bought secondhand and shipped to Panama, their ribbed walls becoming weatherproof canvases. Their mounted speakers drown out honks with salsa, reggaeton, or anything with a vigorous rhythm. Each bus is as distinctive as the tastes of its owner.

|

| Diablo rojo, Panama City bus, with bubble skylights. Via España. |

Yet the diablos rojos of Panama City now face a fate similar to that of the t-rexes that their exhaust systems mimic: their extinction is imminent. Despite the diablos rojos’ festive appearance, their darker side — the lack of maintenance, the ghastly traffic accidents from aggressive driving, the seats made to accommodate the little femurs of children — has led the city to implement a project to replace them with modern, artwork-free, air-conditioned buses that appear as if plucked from the streets of Paris or Madrid or New York.

I had caught the city briefly when the new fleet, the Metrobuses, had yet to take over all the old routes. Thus, both old and new buses were running simultaneously. Panama’s past and future were traveling down Via España literally side by side in an awkward passing of the torch. Almost everyone in the city has been affected: three-quarters of Panamanians do not own cars. Two generations of Panamanians have grown up with diablos rojos — grooving to their music, admiring their bubble skylights, chastising their drivers. My timing presented a rare opportunity to explore how the capital’s residents have been digesting the change.

I sat on a nearby metal bench at a bus stop and met Ana, a young woman dressed in a shirt embroidered with the name of a restaurant. I asked her which bus system she preferred. “The diablos rojos,” she answered as a gust of diesel fumes engulfed us. “They are culture.”

|

|

Diablo rojo on Via España. Looking down from a pedestrian overpass, Panama City.

|

The slanted word SCORPION covered the side of a diablo rojo that had just departed. Another waited behind, its chrome hood ornaments of naked angels glistening in the late morning sun. She added, “They are unique.”

A Metrobus, its destination flashing from an LED sign above its tinted windshield, waited even further behind. I asked Ana why she did not prefer the Metrobuses.

“They are…” She hardened her face until one word forced itself out. “Sober.”

As the line of passengers slowly snaked into the diablo rojo, an airbrushed mural on the side began to appear, featuring a blade-wielding female warrior prowling on all fours, her strap-free thong in the shape of a bat. A soundtrack of thumping reggaeton rattled the frame. It didn’t matter if a passenger was going to work, school, or the fish market: that bus was a roving party. About as far from sober as you can get despite the protests of the blazing daytime sun.

|

| Side panel detail on a diablo rojo. Via España, Panama City. |

The tradition of painting images and lettering to catch attention of passersby extends beyond public transport. A cantina in the country’s interior tends to be announced with freehand block letters; or an airbrushed, anthropomorphic cashew apple (sunglasses optional); or a sweating patron with a wheelbarrow for a beer belly. Cartoonish men in baggy pants drawn next to entrances of barbershops reflect the current trends in Afro-Panamanian fashion. Concrete walls of ceviche kiosks come alive with underwater scenes of octopi and conch. Even stylized, hand-painted anti-smoking notices, advertising a law enacted just five years ago, appear on walls of restaurants and cantinas.

The necessarily one-of-a-kind detailing demonstrates pride in one’s establishment in a way that fabricated signage cannot. For an owner of a diablo rojo, this pride often arises from the bus’ busy collage of images, offering as many focal points as there are panels and surfaces, yielding a sensation that one might receive from the carefully manicured clutter of posters and keepsakes on display in someone’s living room. That’s right, have a look, check me out.

As I watched each bus arrive, something else tugged at me. Diablos rojos didn’t just ring in nostalgia for Panamanians. They spoke to my nostalgia as well. Since I started frequenting Panama nine years ago, I’ve viewed the buses as unmistakable anchors of Panama’s sense of place.

And there was another, deeper reason. Underneath the paint and sparkle trim and hood ornaments, the vehicles were the same buses I rode to school, often during covert spitball battles. After all the years, the buses never vanished. They just died and went to Panama.

No matter what wistfulness the diablos rojos inspired, I couldn’t ignore the narrow aisle that was never meant for dozens of standees wedged hip-to-hip. Getting off at one’s desired stop requires all the skill, finesse, and patience needed to extract a single slice of bread from the back of the bag without disturbing any slices in front of it. Meanwhile, the lack of air conditioning has encouraged passengers to keep the windows open, allowing in the air that hangs so thick from diesel fumes that riders can practically chew it.

|

| Diablo rojo with bubble skylights and a shark fin, Panama City. |

The most notable problem, however, is the recklessness of the many of the drivers. Since each bus is privately owned, the drivers often engage their twelve-ton behemoths in what the Panamanian newspaper La Prensa calls “suicide races” to win the next fare. I wonder what pictures the country’s tabloids will splash on their covers when they will no longer have the chance to report on reliably frequent episodes of speeding buses launching pedestrians like soccer balls. Or when a bus’ rusted axle falls off onto the highway. This is good news for drunken participants of second-rate machete fights, who very well may score coveted front-page exposure after all.

***

It was an hour before show time. While following a quiet stretch of Panama City’s park-lined San Francisco neighborhood, I found Orlando, a driver for a busy cross-town route, sitting alone in his parked bus. SHOW was painted in three-dimensional script above one headlight, TIME above the other. His arms were draped over the giant steering wheel in a fatherly hug. He would start his route in an hour.

“I’ll be driving the route for three months more,” he said in monotone, as if occupied with an unspoken consideration. An evil-eyed clown stared at me from the side of the engine hood.

I asked him what he would do after his route was replaced. He answered quickly — perhaps it was what he had been considering — that his bus was one of the few that would start taking tourists around the city. His vehicle would soon be relegated to a retirement similar to that of the last rickshaw in Hong Kong. It would be an ironic turn for the diablo rojo, a vehicle that has hosted a stream of incidents involving curious tourists who have hopped aboard and found themselves pickpocketed or robbed at knifepoint.

As I would discover, the fate of other buses would be less glamorous. I took another diablo rojo (a medieval castle painted above its windshield) heading to Casco Viejo, Panama’s old city, where the neighborhood’s colonial buildings are currently undergoing renovations at an absurdly dizzying pace as if each building were engaged in a feverish race — perhaps a suicide race — with the one next to it. But I got off well short of my destination when I spotted another square-snouted Blue Bird, an American school bus of the 1980s, parked near the curb. Its driver waved me inside when he saw me admiring the puffy lettering that stated his route’s destinations. The letters blocked out the entire top half of the windshield.

The scent of burned oil and stir-fry escaped out of the stairwell. Carlo, a lanky man who had finished his route for the day, had just brought in a steaming container of leon pan mein, a Chinese-Panamanian dish of noodles and a fried egg, from a restaurant across the street. His two sons, ten and twelve, sat on the vinyl-covered seat behind him and proudly recited their knowledge of my hat’s origins. “Coclé,” they announced, correctly identifying the Panamanian province where I had bought it.

Carlo drives part-time and doesn’t own the bus. He is also a schoolteacher, an image at odds with that of the standard, testosterone-fueled diablo rojo driver. He did not seem nervous about how the termination of his route would change his life. “I am looking forward to teaching full time.”

And the buses? “Most will be cut up for spare parts,” he calmly explained, “and the buses in good condition will be painted yellow and will take children to school.” I reflected on how such a rebirth would return the buses to their intended purpose. Still, I also began to wrestle with the uneasy thought of all the artwork being buried under yellow paint. His bus had been decorated inside and out with panoramas of fiery autumn foliage and alpine mountains, scenes tantalizingly exotic to tropical Panama, something to help cool off passengers in lieu of air conditioning. With a swirl of his finger, he told me that an artist usually earns around three thousand dollars for painting a whole bus, and the work usually takes a month.

He pointed his thumb over his shoulder and said, “There is more on the back.” I walked out and found a flaming-hearted Jesus on the emergency exit. With their flat, square surfaces, back doors naturally lend themselves to portraiture. They rise above the visual din of a bus’ decorations and tend to frame the bus owner’s most important statement, one that all traffic behind the bus must notice.

|

| Emergency door Jesus on a diablo rojo. La Exposicion, Panama City. |

I’ve seen that the exit can also serve as a metaphorical door into the values of Panamanian society. From my informal count, the tally of emergency exit Jesi beats out that of Omar Torrijos, a still-beloved dictator from forty years ago; Manuel Noriega, another of Panama’s dictators, his painted image starting to appear after he finished serving time abroad for drug trafficking; and various illustrations of owners’ children. In an engrossing face-off, Jesus even defeated Jennifer Lopez, albeit by a razor-thin one-door margin.

***

“I miss the music,” said Rosalía, a woman sitting near me on a molded seat of the Metrobus, as we rode to the city’s bus terminal for transfers to all locations outside the city. “But I prefer the air conditioning,” she said, holding up her hand to feel the puffs of coldness spilling from the ceiling. At the terminal, she would take a long-distance bus to her family’s ranch in the interior. I was going to transfer to a bus to Penonome, a large agricultural town two hours west of the capital where, like other towns and cities outside the capital, the Diablo's Rojos still roam freely, at least for now.

Traffic weighed down Via España into a slow-motion dance of steel and squeaky brake pads. Boxed in by idling engines, I found it refreshing to breathe in filtered air instead of bitter diesel exhaust. Aside from my conversation with Rosalía, the bus was deathly silent, as if in mourning for the bus it had replaced. “Music is prohibited in the Metrobuses,” she added.

A discussion about her farm morphed into a sharing of recipes. Rabbits were on the menu. Her recipe utilized creatures running wild on her ranch (“I make them in a criollo sauce. Very rich!”), mine using not-so-wild rabbit from my local Queens butcher (“Rabbit ragout”). The exchanging of culinary ideas has been something of a pastime for me on Panamanian public transit, and the Metrobus was no different.

She was dressed in fashionably tight jeans — a Colombian brand if I am not mistaken — a popular choice of urban apparel. A woman was in front of us, grasping a few cumbersome shopping bags between her knees. Next to her, a white-haired man nudged up the brim of his sombrero pintado, a woven hat made in Panama’s interior. His bony frame barely filled out his boxy guyabera shirt. For a moment, it seemed as if the Metrobuses had already been patrolling the streets of Panama City for years.

As much as I had been considering the effect of the Metrobus’ arrival on the Panamanians, I acknowledged that I was also weighing my own feelings. Accepting change may be difficult for a traveler who would prefer to view a place as immutable, its romantic appeal locked in place, just as change could be difficult for a native who grew up with a certain comforting set of sensations. But there is also a rewarding freshness when allowing a place to take one where it wishes, as when I realized I could observe, from the molded seat of a Metrobus, the snow cone carts and the steam table restaurants, and the pitted sidewalks of the capital without choking. Panama City decided that pulmonary distress need not be essential to its daily experience.

The Metrobus is only one arc of a recent tidal wave of modernization in Panama City. Construction of the city’s monorail, which will be Central America’s only subway, was hurrying along at the same pace as the Casco Viejo restorations. The soaring corkscrew shape of the glass-walled Revolution tower, completed in 2011, is already being pimped as one of the city’s symbols. The long-anticipated Canal expansion, to allow passage of wider ships, has begun. Should Panamanians not also feel pride for having removed some of the biggest polluters from the streets when they breathe cool, fresh air during their daily commute across their capital?

***

It was mid-morning in Penonome, and the town’s central plaza, Parque 8 de Diciembre, swarmed with a crowd circulating around a few hundred canvases clipped to fences and concrete park benches. Birds in the trees whistled in vain against the flute-fronted jazz band performing in front of the cathedral. Penonome’s sixth annual Arte en el Parque (Art in the Park) Festival had just begun.

Artists from several areas of the interior had arrived to sell their latest works. One piece depicted Kuna and Ngobe women dressed in traditional dresses, the bright designs of the garments abstracted into bars of color. There were scenes of farmers harvesting cane, a fantasy image of a woman riding a scarlet macaw, rider and beast content in a comfortable symbiosis, a dreamy, monochrome street scene from a glorious Casco Viejo in the 1950s — a timely choice. In contrast with the art of diablos rojos, the festival's art represented a wider pool of viewpoints, including those of Panama’s women.

I am always intrigued when diablos rojos turn up as subjects of Panamanian art. Art reflecting art reflecting life. Earlier in the week, I found a mural painted by Purple King Crew, a group of Panama City artists, on an outdoor basketball court wall in the capital. The crew paid tribute to Panama’s folklore, including illustrations of molas (geometric, reverse-appliqué designs of the Kuna Amerindians), wooden drums of tipico music, and a diablico sucio (a papier mache mask worn at folkloric fiestas). A diablo rojo, its roof studded with bubble skylights, emerged from one side of the mask, elevating the vehicle to the stratosphere of Panama’s most treasured cultural institutions.

|

| A mural from Purple King Crew adorns a wall overlooking a basketball court in Casco Viejo, Panama City. In this mural that celebrates Panamanian culture, a diablo rojo appears on the left. |

As I was browsing the art around Penonome’s Parque 8 de Diciembre, I spotted a canvas framing the action of a diablo rojo stopping by the predominantly Afro-Panamanian shanties in Panama City’s neighborhood of Curundú, a route now covered exclusively by Metrobuses. In the panel, a gold-toothed man was hanging out of the bus’ doorway while shouting the route destinations, his arm extended in tireless conviction, a flattering rendering of a man whose job title is known in Panama as the pavo — the turkey. The title of the piece: Extinction.

Not only was the route’s diablo rojo extinct but so was the route’s turkey. Metrobuses do not have them. “The spirits of the diablos rojos live on with the drivers. Many are now driving Metrobuses,” a voice said from over my shoulder. It was Reynaldo, the artist of the piece.

He sensed I was not convinced. His eyes began to probe me with a grave, almost pleading urgency. He switched to stumbling English, as many Panamanians tend to do with me, no matter how much I attempt to keep the conversation in Spanish. “The bus is — just a bus. It’s the people who made the diablos rojos special.”

***

“Calidonia, Calidonia, Calle 12, Calle 12!” went the machine-gun shouts of the turkeys. I had returned to the same stop on Via España where I had met Ana, the same one where I had perched every time I’d traveled to Panama for the past nine years. Panama gained control of the Canal Zone in 1999. However, the main arteries of Panama City still follow the squashed contours of a thin strip of coastline that ran under the American-administered Zone. Via España is one of those arteries, a prime place to observe more than half of the city’s buses easing through the bottleneck.

|

| Diablo rojo. Via España. |

Panama is one of many countries to recycle American school buses. Guatemala, Nicaragua, Ecuador, and several other Latin American countries also transport their people in thirty-year-old Blue Birds. But Panama’s are the most wildly painted, sparkle-trimmed, bubble-skyroofed, reggaeton-shaken, Christmas tree-lit vehicles out of them all. And they will be the first to disappear.

It was fitting that one of the first buses that stopped wore LASTIMA QUE HAY QUE MORIR — pity that one must die — across the bottom of its windshield in wide, outlined letters. But why must the diablos rojos die? Why couldn’t the city have instituted a program to regulate the diablos rojos, mandating maintenance and paying the drivers a fixed salary to eliminate the suicide races? It would be easy to say that the arrival of the Metrobuses resulted from political will. Still, a more complete answer may also include what Reynaldo had told me: it’s the people who made the diablos rojos special. The people who have been squeezing in next to their fellow riders for decades, yet always making room for one more, in a disarming sense of community.

Another bus arrived with the slogan of USTED DECIDE, you decide. Modernization may mean different things depending on whom you ask, but only a Panamanian can decide if she is less Panamanian without diablos rojos.

I had been at the stop to photograph the buses one last time, but I felt oddly compelled to board USTED DECIDE, for what could be my last ride in a Panama City diablo rojo. As I stepped up the stairwell, I recalled a conversation the day before with a street artist who goes by the nickname of Rubén Darío (the name of a Nicaraguan poet) on the stoop of the decaying but soon-to-be-restored Casco Viejo building where he currently squats. Rubén enlightened me with the mention of artistic depictions of the diablos rojos that differed significantly from those of the mural on the basketball court. He told me of an underground metal band, his friends performing a song about a diablo rojo driver who boasts a monstrous appetite for running over pedestrians. And another, a song from local grind core band Cadejo, whose YouTube video lays out a string of gruesome pictures of diablo rojo accidents culled from tabloids.

I shook off the images as best I could and seated myself. Standees filled the aisle and pinned me in. I scanned the walls, half-expecting to find dried-up, decades-old spitballs. The boxy seats, the topologic tangle of hips and elbows, the pedestrians outside turning their heads toward the hood ornaments — the shell of the Blue Bird felt like an anachronism, as if it had been dialed up from memories of Panama’s past. And my past.

Then, a reality check. I had not read the bus’ destinations, nor had I listened to the squawks of the turkey. I didn’t know where the bus was going.

That was when I realized I was already where I wanted to be.

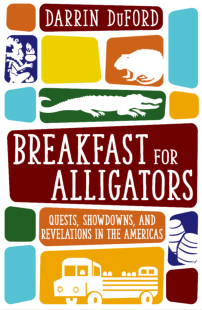

Darrin DuFord is a travel writer, mapgazer, and jungle rodent connoisseur. A past contributor to Transitions Abroad, including "Edible Culture: Ten Creole Specialties to Try in Martinique," he has also written food and travel articles for The San Francisco Chronicle, BBC Travel, Gastronomica, and Perceptive Travel, among other publications. He is the author of "Is There a Hole in the Boat?" "Tales of Travel in Panama without a Car," and silver medalist in the 2007 Lowell Thomas Travel Journalism Awards. Read his latest ruminations on travel and food on his blog, OmnivorousTraveler.wordpress.com , where you can also see his many publications, with the most recent being "Breakfast for Alligators," which we strongly recommend.

|