Sunrise and Ruin in Gorkha, Nepal

Article and photos by Ellie Walsh

|

|

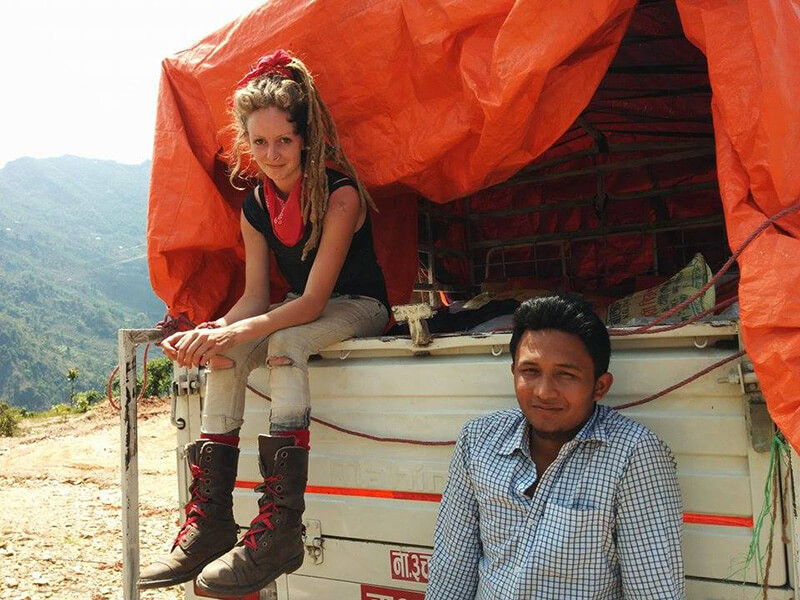

In Nepal, post-earthquake, with vehicle and experienced driver.

|

The sound of my name being hissed cuts through my sleep. My eyes snap open to see Swaraj’s round, bespectacled face inches from mine as he leans over me. I’m wrapped in a ball under my jacket in the doorway of a shed, frozen to the stone floor, and pain grips my joints as I try to uncurl. I groan loudly.

“Ellie,” Swaraj repeats, tugging at my jacket, “I want to see my house. But I am little scared. Please, will you come?”

It’s around 40 hours since the 7.8 earthquake ripped its way through the central region of Nepal and pitched the country into a state of chaos and devastation. Where we lived in Chitwan (the jungle region of the Terai belt), the damage was relatively under control, and most houses were intact. News filtered in of the destruction near Gorkha on the first afternoon as we dithered around and set up camps outside, unsure of the disaster protocol. However, some groups of locals with good navigational skills and some spare cash had taken the initiative. The groups filled jeeps with emergency supplies and drove straight to Gorkha, the earthquake's epicenter.

Swaraj, too, had urged a group of my friends, his old classmates, to accompany him to his village in upper Gorkha. He wanted to take food supplies and see what had become of his family home, the house he had been born in and lived in for twenty years before moving to Chitwan to attend college. His family was safe, but that was all his information, and he was scared.

“Swaraj really wants you to come,” my roommate Nitesh told me the previous morning as they prepared to leave. You come, all of us together. We stick together, right?”

“Do I know Swaraj?” I asked.

“He said you meet at harvest, last year. When you sleep outside for the rice cutting. You stay up late one night, talk about cereal.”

“Hmm, I definitely had a late-night chat with someone about cereal,” I recalled. Much as the tales of horror filtering in from Gorkha made me nervous, I certainly didn’t relish being stuck in Chitwan alone, with no work and no distractions to stop worrying about the others. Besides, I thought I should at least try and help. I was as capable as the boys of carrying a box up a hill. How hard could it be?

The truth was, I had Nepal sussed. I’d been studying as a researcher in Chitwan for a long time, working towards a PhD thesis on ethnic conflict and nationalism in the Terai belt. I knew the customs and traditions and was deeply assimilated into the culture. I was used to poverty, as far as one can be, and could eat the foods on the Lonely Planet warning list without getting sick. I lived in a house with Nepali people I thought of as family. I was proud to be treated and trusted as a local. I looked after other people’s children frequently, ran errands for my neighbors, tutored at the local school, and pitched in with farm work. If I ever had a problem, people bent over backward to help me. That’s what Nepali people are like. I thought I had plundered through Nepal's extraordinary, elusive beauty and conquered the experience. Little did I know, the earthquake was about to prove that I was, in fact, standing on the edge of a void of understanding, about to be tipped into the unknown.

|

|

A cram session with three 10th-graders before their English SLC (GCSE equivalent).

|

|

|

Helping the neighbors' children wash apples at the pump.

|

|

|

Harvest time in Chitwan.

|

So, with none of the same planning, resources, or navigational skills as the other aid groups, we loaded ourselves up with boxes of rice, noodles, and tea, hugged our friends goodbye, and followed a brief argument about the dog (which I lost; we left the dog behind). We headed for Gorkha by bus, changing vehicles in desolate towns, abandoned as people had become fearful of their homes. We passed whole valleys filled with rudimentary tents and families walking along the side of the road carrying young children and armfuls of belongings. The scale of the disaster was beginning to sink in, but we’d accessed so little of the national news. I realized now that we knew almost nothing of the danger we would face.

|

|

Our small, disorganized aid group, resting on a road in Gorkha with our boxes of supplies.

|

By mid-afternoon, we had reached the base of Gorkha, where the Chinese Red Cross had set up a primary emergency hospital for those injured. A state of chaos had set in; many people were searching for missing neighbors and family members, and the situation was unraveling faster than any organization could piece it together. None of the vehicles could make it much further than the base. The hill region was vast and dotted with hundreds of villages, many desperately needing assistance. Still, landslides had blocked most of the roads. Even the NGOs refused to try out the terrain. Groups who had come in vehicles left their supplies with the local police and returned home. Our group set out on foot with no choice but to press on. Swaraj assured us we would reach his village long before nightfall and pointed out that the walk would be nothing compared to the farm labor we were all used to completing.

At midnight, we were still miles from Swaraj’s home. We were reduced to a ragged and exhausted party, silenced by fear. Aftershocks rippled through the ground from time to time, and stones rattled on the road. It was no more than a threatening rumble but enough to make us clutch at each other. We had to scramble over precarious heaps of shrapnel from recent landslides. Trees were uprooted, and cliffs collapsed.

The boxes of supplies became damaged as we lost our footing over and over and even began to spill their contents. Our hands became grazed from falling. Leeches found their way into our shoes, and soon, our feet ran bloody. We tried to work as a team, carrying each other’s boxes and taking turns to have a break. I was walking doubled over with the weight of my pack and the steepness of the gradient, muted from exhaustion, eyes fixed on the dirt beneath my feet to avoid looking at the villages we passed through, house after house destroyed, appearing eerie in the moonlight. Several times, older women came to the roadside and pushed cups of tea into our hands. The locals stared at me with unabashed curiosity, like people had done when I arrived in Chitwan. I’d forgotten what it was like to feel like an outsider.

|

|

On the way to Gorkha, we see a badly damaged house.

|

Nitesh was determined that we wouldn’t give up. He sang Bollywood tracks and harvest folksongs, anything to try and keep our spirits up. He retold early memories of our lives in Chitwan together, recalling carefree summers and long, hot evenings by the river to distract us from our weariness.

|

|

Memories of times in Chitwan, helping women prepare for a festival.

|

“First day I met Ellie,” he said, “I was queuing for watermelon stand in market. And I see white girl wearing a baby harness and carrying baby bottle with milk. I am thinking, oh my, I bet her baby is so cute, maybe she make baby with Nepali husband. I really want to see that baby and pinch its cutie cheek. I walk over and look, and oh my, I get such nasty shock! Crazy white girl is carrying black puppy in her baby carrier! She is feeding puppy from baby bottle! I am so mad because I lose my place in watermelon line, just to see dirty dog. Really, it is not good start for making friendship.”

Everyone laughed through their exhaustion and exchanged stories, but eventually, fatigue got the better of us, even Nitesh. The low point came somewhere around 2 a.m.; we had to stop at the side of the track while I collapsed in an untidy heap and dry-heaved (a combination, I suspected, of altitude sickness and shock) over the hill's edge. At the same time, Nitesh sat exhausted beside me with his head clamped between his knees and his hands tight around my wrist to stop me from falling.

I’m ashamed to say that at that moment, I regretted leaving the comparative safety of Chitwan. I thought of our home on the riverbank; the little mud house with the courtyard and water pump, my shiny white bicycle leaning on the kitchen wall, and the lemon tree creeping in through the window. I thought of my dog and the children we had left behind, who would be missing us and scared of the aftershocks. I looked at our miserable packs of food and wondered why we had even tried to help. Swaraj crouched down next to me and put his arm around my shoulders.

|

|

Memories of times in Chitwan, making a pancake mix in the yard outside our home.

|

“Doing so good Ellie,” he murmured. “Really, you are brave to come here. You are good friend to Nepali people. Now, let’s go. We must beat the aftershocks!”

Everyone was so sure that I could be smart and brave. Yet, I began to realize it was impossible to be both simultaneously. Just because I thought of Chitwan as home didn’t mean I had the whole country figured out. I may as well have been on the other side of the word right, for all that was familiar to me in Gorkha. But the fear of burdening my friends when they risked their lives to try to help was enough to get me to my feet.

We pressed on for another hour, pulling each other by hand. By the time we reached the edge of Swaraj’s village, we were too drained to feel any sense of accomplishment despite the impressive terrain we had covered as one of the first groups to make it out beyond the bazaar. Swaraj quietly suggested that we wait until morning to go to his house, as it was too dark to see anyway. We collapsed like dogs in the nearest shed and fell into a deep, troubled sleep.

Now, just three hours later, peering out from the collar of my jacket as Swaraj tries to get me back on my feet, I can see the sun cutting its way across the valley. Just to the left of my head, a tethered buffalo calf glares at me while chewing with its mouth open. I wrinkle my nose at it.

“Was that here all night?” I ask Swaraj. He laughs.

“Come,” he says, holding out his hand. “Please, Ellie. We go to my home, together.”

I get to my feet with some effort, the ache of yesterday’s walk, and a lack of sleep deep in my joints. The overload of yesterday’s adrenaline has left me feeling shaky, almost hung over. We step out of the buffalo shed and onto the stone porch where the others are sleeping. Nitesh is on his side, rigid against the cold, and curled against the other two boys, sharing a coat. They look strangely aged, older than yesterday, their faces patched with dirt, frowns cut into their brows.

I follow Swaraj in silence through a maze of paths that cut between the rice fields and along the edge of a low wall. I can feel the tension in Swaraj’s step; his fists are clenched at his sides, and I link my arm through his. We round the corner of the wall and see Swaraj’s house appear. We are facing the back door, which is set deeply into a chunky wall made from proper brick, much stronger than the houses in Chitwan. It’s the only wall still standing. The rest of the house has collapsed beyond the parameters of the fence around the garden, rubble heaped in every direction, and wooden beams at all angles. The upstairs spills like an open wound. Half a bed frame hangs from a length of plaster; bits of timber are recognizable as the remnants of cupboards and doors.

I have one hand gripped hard over my mouth, the pain in my legs and back suddenly gone, my knees shaking slightly. This was all his family had. I look across at Swaraj. He shrugs and smiles at me. How one might react to being told their favorite mug had been smashed. I clench my jaw, feeling like a child in the playground, trying not to cry, ashamed of my weakness in the face of his bravery.

“It’s ok Ellie,” he squeezes my hand. “Really, it’s ok. We will build another one. No problem. Maybe government will help. It is only house. People are safe.”

I’m frustrated at my sentimentality. I’ve never seen anything like this before. I know that this is all wrong, that it’s the wrong way around. It should be me comforting him, smiling, and squeezing his hand. His strength is unfathomable.

The sun pushes further up the horizon, and the air turns a hazy gold. It’s the first time I have seen Gorkha in morning light, crisp and unnervingly silent. After living in the humid, flat lands of the jungle for so long, it’s utterly captivating. The hills tumble on forever in front of us. For the first time, I understand what brings thousands of tourists to Nepal every year in search of panoramic visions. The view is cripplingly beautiful yet so hard to make sense of, the tranquility of the rice paddies, the little lanes and herb gardens, the vast rolling hills, and the awful destruction of the homes, heaps of rubble, salvaged possessions piled up in doorways. Swaraj gestures across the landscape with a swell of pride.

“This my home, Ellie. I grew up here.”

I don’t trust myself to speak.

“I am so happy to bring you here,” he continues. “You are first foreigner to ever come here! Great, right? Today, when we do food drop, you will see many beautiful places. And my neighbors will feel excited to meet you!” he smiles.

Despite the pain in my legs and feet, which are swollen and scabby in my boots, I feel cheered at the idea of taking our food to the locals, though I have no idea how we will manage more walking. It’s hard to feel worried about more aftershocks, landslides, or blocked roads when Swaraj’s calmness is so contagious.

Suddenly, Nitesh and the others bound around the corner looking grubby and cheerful, spilling steaming chi tea in tin mugs.

“Oe! Sorry about your house, brother,” they say in Nepali, clapping Swaraj on the back and handing us a cup of tea each. “There things happen. Happen before. Happen again in future.”

“What’s wrong, Ellie?” Nitesh asks, seeing my tear-filled eyes. I duck my head in embarrassment.

“Oh, she is just missing her dog,” Swaraj smiles.

“Don’t feel sad Ellie,” Nitesh jokes, “good story for your thesis, no?”

We stand and take in the view together in companionable silence, our arms looped over each other’s shoulders and the wreck of the house behind us. My mind is already straying to plans of going home, organizing a proper relief effort, and returning in a vehicle when the roads are cleared. But now, I feel as though I’m breathing the cleanest air I’ve ever breathed, standing on the edge of something huge, caught somewhere between one world and another, leaving a country that would never be the same again, stepping into a new era, hoping that I am about to play a tiny part in rebuilding Nepal.

|

|

Drop off of proper food supplies to villagers after a landslide.

|

|

Ellie is a PhD student at Plymouth University, UK, where she explores and analyses poetry written by low-caste women from the remote regions of Nepal. Following the earthquakes in 2015, Ellie has been focusing her efforts on assisting and educating children who work in bonded labour in the Terai region. On completing her PhD she hopes to move to Nepal permanently in order to continue working for children's rights.

|

|