Long Live Pakistan

Article and photos by Sonya

Spry

|

|

First mountain views in Pakistan.

|

Traveling anywhere can be risky if you don’t do your homework beforehand. Government organizations are overly cautious, the media sensationalizes, and second-hand travel stories are often exaggerated. The best advice is to read up on where you want to venture, heed the warnings, and keep alert, but do not allow anyone to dissuade you from following your travel dreams.

After selling all our possessions in 2006, we handed in our rental keys to the none-the-wiser woman behind the counter at the Arnhem council office in The Netherlands. We could hardly envisage what was in store as we went down the bike path and across the German border to distant Pakistan. About one thing we were certain: the much talked about Karakoram Highway would be one of our biggest cycling challenges. That was why when we finally reached 18 countries almost a year later, realizing our dream became more than a dilemma over whether to cross the border.

To Follow Your Dream or Not?

Tashkurgan, bordering western China and northern Pakistan, is not a raging metropolis. In fact, apart from a single crossroads of activity, where you can purchase almost anything you need, everywhere else is pretty quiet. Photocopying documents is out of the question due to a malfunctioning machine. The bubbled tins of tomato paste, stamped with use-by dates from early 2006, are unmistakably dubious. On the other hand, there is a small market with plentiful supplies of shopkeepers sporting broad smiles and reasonably fresh products. On the junction, pool tables stand out in the open air, further warping with every breeze. Goat skins hang from the peddler’s arms. And a hearty lagman soup made of meat and thick noodles, which you can slurp up with as much noise as you like, costs just US$0.75.

|

|

Shopkeeper in Tashkurgan.

|

Up until two days ago, we had pedaled just 293 kilometers (180 miles) of the infamous Karakoram Highway: a 1,200-kilometer-long stretch of road beginning in Kashgar, China, and ending in Havelian, Pakistan. As the highest paved international road in the world, it is no surprise that this pathway is a touring cyclist’s dream just waiting to be conquered. Snaking its passage around some of the tallest mountain ranges in the world, the highway is renowned for its instability and subsequent landslides. The ever-changing landscape must never cease to amaze locals and Chinese road workers alike. For us, being crushed by the mighty force of nature is the least of our concerns.

Just a week before we had arrived, a bloody aftermath resulted when government security forces and militants came to loggerheads at the Red Mosque in Islamabad. A day before we arrive in Tashkurgan, suicide bombers strike in two isolated incidences in the North Western Frontier Province. And tomorrow, three more bomb attacks will confirm that there is definitely enough tension in the air in Pakistan for us to feel some trepidation about entering the country on a bicycle.

Instead, we enter the internet café looking for news updates. Still, with China’s strict internet censorship and prolonged landline connections, finding out much more than we already know isn't easy. There are also very few posts on the usually helpful travel forums. Unplanned pedaling “back to anywhere” is a cyclist’s pet hate. Still, judging from the current travel advice issued by the embassies, we may have to get Plan B up and running.

The Usual Official Humdrum

Australian officials strongly advised to review any decision to travel to Pakistan due to “a very high threat of terrorist attack, sectarian violence and the unpredictable security situation.” The Netherlands’ Foreign Commission echoes this warning. According to both representatives, terrorist attacks can currently occur anywhere in the country, and targeted cities include every central township on the map. They further call for vigilance in basically any place likely to be considered a terrorist target. Ironically, the list consists of their establishments and every public location you can think of. So it is impossible to steer clear of the dangers — unless, of course, you don’t mind starving to death or sleeping on the streets.

Pakistani Independence Day is just under a month away, and more news that militants have a preference for attacking and around days of national significance adds yet another cross to the cons column of our plight. Accordingly, no one is coming out of the country either. We should pack the panniers and return to Karakol Lake by this stage. But something inside both of us keeps the search going — any justification to cycle into Pakistan.

As we exited the internet café the following day, after another few hours of wasted effort, we headed to the hotel room. We resolved once and for all that we had to move forward. We will stay until the weekend and research our exact route more. But unless anything huge breaks out, despite the warnings, despite our path taking us through areas of concern, and, not surprisingly, despite my Mother’s pleading emails to come back home until it is safe, we will head into the 220 kilometers (135 miles) of no-man’s land between Tashkurgan in China and Sost in Pakistan. Due to a few cyclists wandering astray a few years back, the steep mountain corridor that forges you up and over the Khunjerab Pass (4,733 meters or 15,500 feet) is no longer an option to travel by bike. You must purchase a bus ticket.

We wake early, pack, and wheel down the measly (590 meters or 1935 feet) of the barely used, immaculate, double-lane highway towards the bus station. You can purchase tickets in Chinese Yuan, Pakistani Rupees, or US Dollars at the depot. As we hand over a mixture of money, whether we have made the right decision plays havoc with our minds. However, the soon-to-be badger session to get the driver to put our ten Ortlieb bags in the luggage compartments rather than on the bus takes precedence over all other thoughts. Before I pause to think again about our possible vulnerability, we are chugging our way high up to the sky.

So far, we feel safe, though security is tight throughout the trip. There are head counts and passports scrutinized over and re-checked, but nothing quite as frightening as the atrocious condition of the roads in the wild and woolly world that greets us on the Pakistani side. In some sections, there is barely enough room for the bus to pass as boulders as tall as two men wedge their jagged edges deep into the remaining asphalt. We are riding through a quarry site for giants and imagine that, at any moment, a monstrous foot will come crashing down next to the bus, putting everything into perspective. Naturally, it doesn’t, and I spend most of the journey stunned at the endless height of sheer-faced mountains and the magnitude of the damage roadside rubble can cause.

After six hours of highly competent maneuvering, our driver pulls up to the border gate, weighted down by a rusted tin can full of rocks. We are in Sost.

What Is All the Fuss About?

I didn’t expect to meet with open fire nor watch people dashing for cover, but I did think there would be more zest than the laid-back feel this sleepy town emanates. Still, we are in north Pakistan, and trouble has been isolated in areas closer to Gilgit. Maybe we will notice more unrest as we go further south. The biggest fuss over the next few days comes from me as I squeal with glee every time I feast my eyes on a Pakistani truck. The owners definitely have a competition to see who can adorn their vehicles with the most color — more vibrant and entertaining than any pageant float you can imagine.

|

|

A broken-down bus resembling

a pageant float.

|

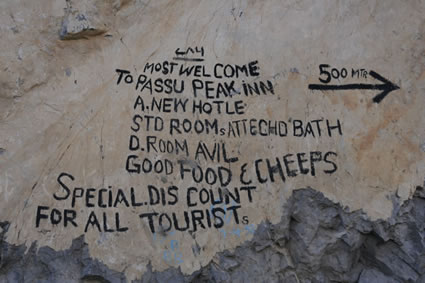

We take it easy pedaling to Karimabad — the Hunza Valley’s Capital — which pleasantly enough is just as relaxing as the unpretentious border village and Pasu — where we came to rest last night. Establishments like Mr. Baig’s Batura Inn sparsely dot the highway, and the one thing they all have in common is that they are empty and want you to stay overnight with them. The facilities vary, so it pays to shop around. Regardless, you will hand over little more than US$2 per night for fundamental accommodations.

|

|

Guests are certainly wanted at

local inns.

|

Mr. Baig, a peaceful man in full Pakistani attire — white salwar kameez, beige woolen vest, and matching beret — has been running his place since 1974. Proudly reminiscing about his business when it was bustling with foreigners, he hands us several tattered books as proof — full of only praise for his services and wealth of knowledge. As we thumb through, it becomes apparent that the entries stop just after September 2004. From then on, only a handful of travelers have passed through.

The same story can also be heard in nearly every guesthouse in Karimabad. And it is no wonder this area is a mountaineer’s and trekker’s paradise. Everywhere you look, you are dwarfed by colossal mountain ranges abundant with dramatic snow-capped peaks stabbing high into postcard-blue skies. Sadly, apart from a spattering of local trade, tourism is pretty sparse these days — which offers perfect evidence that if the only media coverage this country receives is negative, then foreign travelers will remain at bay.

|

|

Mountain range near Pasu.

|

|

|

Outside Karimabad.

|

Yes, There is Some Dangerous Biking Countryside

Our tiny insignificant forms move slowly along the undulating, unguarded track on cliff-face drops that meet the surge of the blue-grey waterway below. There are some smooth sections, lots of bumpy bits, specific segments that don’t resemble a road, and a few spots where nature has reclaimed the artificial terrain as a river.

|

|

Our tiny insignificant form on a bike against the cliff-face drops.

|

We venture into Gilgit and then through to Thalichi — where our lives are threatened by dehydration and overheating in the 55°C canyon furnace. Sweat stinging our eyes, we squint up enviously at the snow-covered Nanga Parbat peak (8,126 meters or 26,660 feet), also called “Killer Mountain,” as it claimed many lives in the first half of the twentieth century. This sure is a dangerous country, alright, but not through any terrorist attack.

|

|

Snow caps above the seering heat

of the canyons.

|

Snow caps above the searing heat of the canyons.

After the heat and exhaustion of today’s cycling, the simple bucket bath at the back of the “soon to be” hotel, the primitive mud floor room filled with charpoys (rope-strung beds), the traditional meal comprising fresh chapatti, and a couple of dishes of okra and tomato-fried eggs are luxurious in comparison.

|

|

With the owners of the "soon-to-be-hotel."

|

We push further towards Chilas, and transport is organized to cross the Babusar Pass. It is just 24 hours before Independence Day, and coupled with entering the Kagan Valley — yet another area allegedly inhospitable for foreigners — we are doing everything the embassies have told us not to do. Apart from feeling a little out of place in Chilas, since not a single woman was in sight, the only problems we dealt with were the continual bus breakdowns over the long and arduous 9-hour, 45-kilometer journey. Attempting to get the bus up the boggy landslides takes several goes. The most successful method is when the first two-thirds of the bus disembarks to assist by pushing from outside. At the same time, the back passengers remain seated for rear traction and the white-knuckle ride.

|

|

Pushing the bus after a mechanical breakdown.

|

After several clashes with boulders and a very nasty odor of a burning clutch, it becomes apparent that the bus is not up to it. Just 1.7 kilometers before the Babusar Pass (4,175 meters), the axle lies split in two, its innards sprawled across the middle of a switchback. We take the crossed-arm signal from the bus driver as indicating the death of our transport. After hauling our gear off the roof rack, the axle was tied back with a piece of string. The bus takes off, looking like it will make it over the top. From this day on, I will place more faith in the Pakistani ability to repair a broken-down vehicle.

We still have to push our way over the top of some rugged and high-altitude terrain before plummeting down the rocky slopes into Gittadas and all the finery and flair of a Pakistani celebration. Tonight, all we can muster up is the search for the food tent, followed by sleep. Tomorrow, we’ll have the loan of a gas burner because our petrol stove won’t work; we’ll be invited to drink tea with officials; and the military will guard our tent as we are ushered into VIP seats for the inaugural event on Pakistan’s Independence Day — the world’s highest polo match between Chilas and Gilgit.

|

|

The Pakistani military guards our tent.

|

|

|

Crowds gather at the world’s

highest polo match between Chilas and Gilgit

|

Keep Living the Dream or Leave?

Time passes quickly for us in Pakistan. Before we know it, our 30-day visa is running out. When we finally make it to Islamabad, we must decide whether to renew it or leave promptly.

On the road, you either contend with the challenge of soaring temperatures, landslides, lack of bitumen, or the complete madness of the toot-happy truck drivers. In any township, you will be the center of attraction. There is friendliness wherever you go, and people go out of their way to help you with anything. People will dart through traffic to come and shake your hand or drop what they are doing to escort you to the hotel you are looking for. You will be called Sir or Madam with genuine concern. Policemen, security guards, and officials smile in Pakistan, and locals yell "welcome, welcome, thank you," as you pass through their village.

|

|

Moral support from the locals.

|

The decision is much easier than we made a month ago: we will stay.

Long Live Pakistan

Making the decision to travel through Pakistan by bicycle, even when the media, authorities, and loved ones warned against it, has taught me some compelling lessons.

Adverse reports of terrorist attacks in far-flung corners of the globe will have the rest of the world in a frenzy. People will start canceling their tours and re-routing airline tickets when their itinerary, more than likely, takes them through areas both politically and geographically isolated from any concern. Put in the hands of the international media, even the most minor incidents are blown far out of proportion. So significant are the distortions that it could well appear — from the comfortable confines of your breakfast table — that an entire country is focused solely on mass destruction.

Foreign Embassies have to do their job: they have little choice but to be politically and responsibly correct as possible.

And then there is darling Mother, safe in the confines of the home zone, reading about all sorts of tragic destruction in a country where her daughter intends to bicycle. Of course, there is a significant fallout in the form of those influential emails pleading surrender to a safe haven.

But once you remove the sensationalism, the suspicion, and the dramatics, the problems caused by minority groups should not be enough evidence to keep you from experiencing a new culture. I felt safer wandering Islamabad's streets at night than in East Hastings in Vancouver, Canada. Ask the brave few what they thought about Northern Pakistan, and they will tell you it was magical. At least, that is what we say when questioned about the place.

In fact, we would go as far as to say that it was one of our most treasured journeys in the “what a wonderful world tour” to date, and we have already penned in our return trip. This time, we will read the media and take the hysteria with a pinch of salt; we will look at the embassy’s travel advice warnings and note them in our minds. We’ll not tell my Mother until we cross the border.

However, our individual convictions are totally ineffective on a large scale. There is still such a lack of confidence from the majority of the world that the primitive infrastructure already in place in Pakistan is slowly dying at the hands of this speculative negativity. With my own eyes, I saw what an effect it had had on the tourist industry. While I am the first to wave my hands in the air and shout, “don’t forget to add Pakistan to your list of places to visit,” a part of me doesn’t mind if you don’t. Tourism can bring about changes that indisputably damage natural beauty and cultural atmosphere. Selfish as this may sound, we will have the place to ourselves again on our next trip in two years. If you dare to visit the land, you will be chanting “Long Live Pakistan” along with us too.

|

After leaving the so-called life

of normality behind in 2006, Sonya Spry has since been cycling around the globe with her husband, Aaldrik Mulder, writing about their cultural adventures and bike-touring escapades.

|