In the Vale of Kashmir

By Mark Hawthorne

|

|

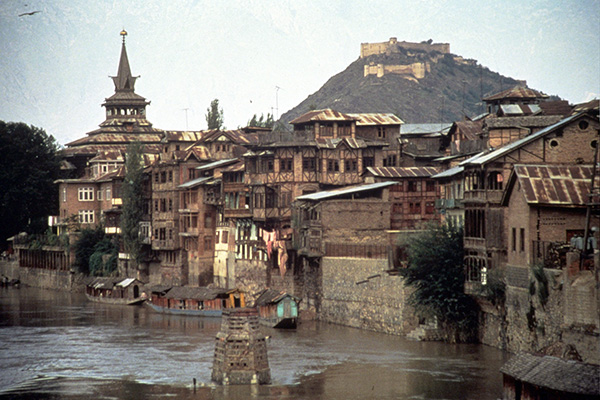

The city of Srinagar, Kashmir. Photo by Lynn Bishop.

|

Only upon landing at the Srinagar airport did I realize just how blindly I had ventured into Indian-controlled Kashmir, knowing so little about the region flanked by Pakistan and China. But I was eager to spend time on a houseboat on fabled Dal Lake, so, stepping onto the tarmac, I focused on the beauty of the surrounding Himalayas even as I felt anxious about the Indian security forces, the barricades and the razor wire. Kashmiri extremists were struggling to wrest the territory from India’s control, a fellow passenger told me, and violence was not uncommon.

Undaunted, I found lodging on the Gemini, a five-bedroom houseboat owned by Bashir Shaala. Bashir had built the Gemini in 1983, shortly before the separatist movement brought fighting to the valley and transformed Srinagar, Kashmir’s capital, into a battlefield. He appointed the houseboat with Kashmiri carpets, chandeliers, and furniture that was reminiscent of the days of the Raj. Anchored beneath the shade of an island tree, the Gemini floated permanently on the lake about fifty yards from shore, which was reached by gondola-like boats called shikaras. I certainly felt spoiled during the day, but at night, I lay awake, listening to the gunfire from Kalashnikovs and wondering just how bullet-resistant the Gemini’s hand-carved walnut paneling was.

Bashir’s nephew Manzoor often visited. An outgoing medical student of twenty or so, he was very self-possessed for so young a man. A thatch of black hair topped his tall, wiry frame, and a neatly trimmed beard gave him an added appearance of maturity. Manzoor spoke softly in fluent English of the things that mattered to him most: his family, medical school, and Islam. I sensed in him a decency and fidelity that gave me hope for Kashmir.

|

|

The nephew, Manzoor, a medical student. Photo by Lynn Bishop.

|

“Would you like to visit my house tomorrow?” Manzoor asked me late one afternoon as we sat on the verandah. “It is not far from Srinagar.”

“Yes, I would. Very much.”

“I will come by tomorrow morning. We can take the bus to my village.”

All the seats on the small bus were taken, so Manzoor and I stood at the back and hung onto a rail, subway-style. More passengers boarded at each bus stop, which seemed to be spaced twenty feet apart, and soon, all the real estate on the bus that any reasonable person would consider available was occupied. Our bus driver, however, continued to stop for passengers, who didn’t appear to mind the utter absence of a comfortable place to sit or stand. Yet, the sheer volume of humanity kept everyone vertical. The passengers wedged against the windows obscured our view of the outside world. Nevertheless, a remarkable homing skill allowed Manzoor to sense when we had reached the stop for Shalimar village. “We get off here,” he said, and I followed him, squeezing through the crowd.

Manzoor’s home was set back from one of the village’s main road, little more than a dirt path. The single-story house, painted a pale shade of brown, would have blended right in with half the neighborhoods in the U.S. I briefly met his mother, two sisters and grandmother, who then disappeared to prepare lunch. The women would bring lunch, Manzoor explained; after we finished eating, they would eat what was left. As we sat on his bedroom floor, a naked light bulb dangling overhead, I was surprised and flattered to learn I was the first Westerner to visit Manzoor’s home. Not many travelers ventured out this way, it seemed. He brought out the family Koran, printed in Arabic. I removed an India travel guide from my daypack. I told him what the Lonely Planet editors had to say about Islam. He kissed the page and touched it to his forehead. There was a knock at the door.

“Ah, lunch,” he said.

Manzoor’s older sister brought in a large pewter bowl. Following Manzoor’s lead, I washed my right hand — the only hand for eating; the left hand is reserved for hygienic functions. Next, she brought us a couple of metal plates and two metal cups, took the pewter washing bowl, and finally returned with a large plate of food.

Not using both hands was a struggle, but using the left hand during a meal is taboo, so I sat on it. I scooped small bits of steaming-hot mutton, rice, potatoes, and sauce, much of which landed back on my plate. Meanwhile, my host adroitly hoisted handfuls of food to his mouth, washing it with the cold tap water filling our cups. I was thirsty but wary; I had managed to avoid getting sick in India by filtering all my water.

“The water is treated,” Manzoor assured me. “Go ahead and drink.”

I knew the toilets on the Gemini emptied right into Dal Lake. “Manzoor, please understand. You’re used to the water. I’m afraid I’ll get sick.”

“But you are a guest in my home,” he pleaded. “I would never make you sick. It would not be honorable. You must trust me.”

“Oh, great,” I thought. “Now it’s a point of honor.” I took a few tentative sips, imagining a legion of bacteria invading my virgin stomach like Mongol hordes attacking China, eventually making camp in my lower intestine. The water certainly looked clean. And it tasted fine. After the hot lunch, no water had ever tasted better. The honor was maintained, and I’d be able to confidently make the trip back to the Gemini.

Manzoor was eager to show me the village, so we walked down the dirt road after lunch. Women covered from head to toe in dark burkhas passed us, and children followed me, giggling. Unlike the urchins I’d encountered in other parts of India, these kids didn’t ask for rupees; they seemed content to see a foreigner. We stopped at the seventeenth-century Shalimar Bagh, a verdant garden of trees, flowers, and grass neatly landscaped around a large central fountain. Relaxing on the shaded lawn, I began to sketch one of the Mogul structures in my journal, and some of the children gathered around me; they leaned over my shoulder and watched as I drew the building’s thick columns, ornate details, and the surrounding juniper trees.

“Do you think the terrorists will ever leave Kashmir?” I asked Manzoor.

“I can only pray that the violence will stop,” he said, his voice rising from a deep well of sadness. “Everyone seems to want all of Kashmir: India, Pakistan, China. Many Kashmiris want autonomy. I do not know what will happen here.”

Following India’s independence in 1947, the country was partitioned into nations of Hindu majority (India) and Muslim majority (Pakistan). However, the question of where Kashmir should end up was never settled. The coveted territory, endowed with a mild climate and fertile soil, was split and has since become a point of contention in the subcontinent.

I finished my sketch, and we sat silently for several moments, enjoying the jasmine-scented breeze. Manzoor poked at the grass, staring across the garden. “Let us go to my uncle’s house,” he suggested. “He is an archeologist.”

Another half mile down the road brought us to a small house surrounded by rose bushes. An elegant-looking man answered the front door, and Manzoor introduced us. Tall with deep-set eyes, Manzoor’s uncle wore a white kurta over his lean frame, and a long ebony cigarette filter dangled from his lips. A dark mop of hair made him look a bit like George Harrison.

“Come in,” he said. “I am just having tea.” We left our shoes on the stoop.

The living room was furnished with white throw pillows lining one wall. Another wall was made up of books, row after row, shelved into a recessed bookcase. Manzoor and I sat on the carpeted floor while his uncle disappeared behind a translucent screen trimmed in rosewood.

“I will be only a moment,” he said. He returned carrying a large silver tray on which he balanced a pot, cups, saucers, and a small plate of cookies. “I hope you like Kashmiri tea,” he said, filling my cup with the green beverage. “How are you enjoying Kashmir?”

“It’s beautiful, though I see a lot of soldiers and checkpoints in Srinagar. Is it really that dangerous?”

“Sadly, yes,” he said. “Of course, this was not always the case, but the Kashmiris are very passionate about the issues they have had to face lately, with so many laying claim to the territory.”

“How has it been for you? Has all the trouble affected your work?”

“Oh, I should say so,” he said tersely. “I have been invited to speak in Japan and Washington, but the Indian government will not permit me to leave Kashmir.”

“Are they afraid of what you might discuss outside India?”

“No, they are afraid I might never return! An absurd notion, really, since my life’s work is right here. This is the ideal country for an archeologist. We have a history dating back thousands of years — empires that existed long before the great civilizations of Europe. And since archeology has only flourished in India for less than a century, we are in the infancy of our craft.”

His words brought to mind the remains of a footbridge that had spanned Srinagar’s Jhelum River. I’d seen the empty stone pillars a few days before and asked a local saffron merchant what had happened to the rest of the bridge. “Blown up by terrorists,” he’d said with both grief and disdain. I could only imagine how much of Kashmir’s proud heritage was being lost to make a point.

“What do you find the most rewarding about your work?” I asked Manzoor’s uncle. He took a long draw on the cigarette while considering my question.

“Tell him about the monasteries,” Manzoor said.

“Yes, the monasteries. Fascinating. I have visited all the monasteries in Ladakh. Do you know Ladakh? The people are Buddhist east of Kargil, and there are hundreds of gompas, which is what they call their monasteries. Here, let me show you.” He rose and searched among his books, retrieved a scholarly tome titled simply Ladakh, and set it down before me. One page featured a picture of several whitewashed buildings perched along the crest of a pleated hill. “That is Lamayuru Gompa,” he said. Ladakh looked like nothing I had ever seen: dazzling Himalayan peaks scraping the sky; florid, robust people; adobe monasteries hidden in the clefts of mountains; and an arid landscape that ranged from lunar to simply heavenly.

“It looks wonderful,” I said, understating Ladakh’s obvious merits.

“It is indeed. Except for the Vale of Kashmir, Allah created nothing comparable. You really must see it for yourself. It is, I should add, much safer in Ladakh.”

“

“This seems like a very thorough book on the subject.”

“It should be,” Manzoor said. “Uncle wrote it. Along with most of those others you see.”

Two days later, I struck out for Ladakh, determined to explore a land that Buddhists say is what Tibet was like before the Chinese occupation. Sailing from the Gemini to shore on a shikara, I gazed at the bullet holes in the waterfront hotel just ahead, then turned to look back at the houseboat. Bashir and Manzoor waved goodbye from the verandah. I felt a little ashamed, as though I’d abandoned them. Yet the danger to travelers was undeniable; indeed, the November 2008 mayhem in Mumbai — and India’s accusation that militants with Kashmiri ties were behind it — has only escalated the tension. The State Department is strongly urging U.S. citizens to avoid travel in Kashmir. I waved back, already missing these warm people who wanted nothing to do with the narrative of hostility that had blackened their homes.

“We desire only to live in peace,” Bashir told me the night before my departure. “It is up to Allah and the Indian Army if that peace ever comes to Kashmir.”

Mark Hawthorne’s writing has appeared in Hinduism Today, Satya, VegNews and in the anthologies Stories to Live By (Solas House) and The Best Travel Writing 2005 (Travelers’ Tales).

|