Madaba: Jordan's Mosaic City

Article and photos by Daniel Gabriel

|

|

This portion of Madaba's famed Mosaic Map shows boats and fish in the upper Jordan River, as well as several nearby cities.

|

One of the joys of travel is discovering the key that unlocks a particular locale, or community. In Madaba, Jordan, there’s no secret to this. The answer is right at your feet: it’s all about mosaics; 1400 year-old mosaics. This isn’t simply some long-dead art form trotted out to visitors, but a vibrant expression of culture that is still being taught and produced by locals and for locals — as well as to the lucky travelers who stumble upon its charms.

Madaba is little more than half an hour southwest of Jordan’s capital, Amman, but the city of 100,000 has more in common with a provincial Greek town than it does the sprawling, concrete block masses of Amman. Founded 4,500 years ago, Madaba flourished during the Byzantine era as a regional center of religious life before being destroyed in an earthquake in the 8th century AD.

Unearthing the Past

|

|

Given how much remains buried beneath the sands, Madaba's mosaic legacy will continue to grow.

|

It lay fallow and forgotten for over a thousand years, until a late 19th century dispute between Christians in another area of Jordan led to a request for the Ottoman rulers to allow them to separate and found a new city. The Ottomans were tolerant of the faith, but not inclined to encourage its spread. By law, no new churches could be erected — except on the sites of former edifices. This led the fractious group back to the historic Christian city of Madaba, where many such churches were buried somewhere beneath the sands. Once foundations had been located, and digging began, marvelous discoveries were made. There were intact mosaic floors still in place throughout the former city area. While many were Byzantine — and of a very high standard — others were pre-Christian. Roman roads were uncovered, and private homes bearing their own prestigious mosaic floors, which served in place of carpets as central motifs for decoration.

The biggest find of all surfaced in what is now the Church of St. George. This was the legendary Mosaic Map of the Holy Land — the oldest known map of the region. Originally measuring a staggering 50 feet by 20 feet (though only portions remain), the 6th century Mosaic Map depicts sites all the way from the Nile Delta to northern Israel. The walled city of Jerusalem, St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai, the Jordan River . . . it’s all there. When it was first unearthed, archeologists rejoiced to pinpoint the site of the vast Nea Church in Jerusalem, the largest Christian sanctuary ever built to that point, and long since disappeared.

Visitors intent on truly studying the wealth of mosaic styles and remains can spend days — or weeks — exploring. The best known sites include:

- the 6th century Church of the Apostles, which houses one of Madaba’s most elaborate mosaics — “Personification of the Sea,” a medallion depicting a woman emerging from the waves, surrounded by aquatic creatures;

- the Church of the Virgin, which was the first church discovered in Madaba when digging began in 1887 (it too was originally built in the 6th century — on top of a Roman temple);

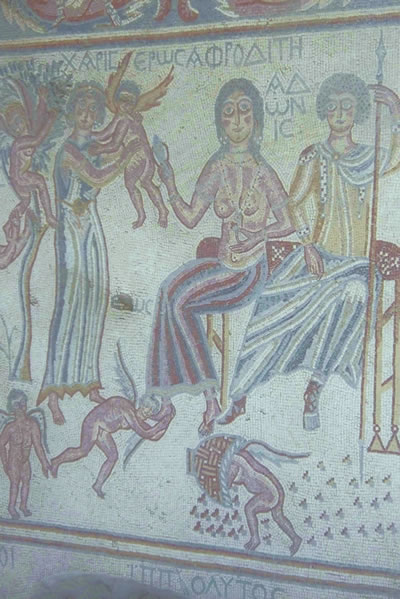

- the Hippolytus Hall, a former Byzantine mansion with extensive classical Greek motifs, including some rather playful images of gods and royalty.

But the discoveries are far from over. When we stopped in at the Madaba Archeological Park, we checked out a variety of Roman bath mosaics, and a long Roman road going out beyond the Burnt Palace. One of the guards called us over and began digging under various bits of sand to show us that mosaic floors lay unexposed beneath mounds in all directions.

|

|

On this mosaic in the Hippolytus Hall, the god Eros and his buddies frolic with the fashionable set.

|

Modern Mosaic Studies

An additional satisfying aspect of Madaba’s mosaics is that townsfolk even today are engaged in creating them. While some of this produces rough-and-ready knock-offs bound for one of the many craft and antiquity shops along the main drag of Talat and Al-Husain ben Ali streets, there are two sites worth singling out.

One is the Madaba Institute of Mosaic Art and Restoration. Established in 1992 by the Italian government, and now run by Dr. Khalaf fares Al-Tarawneh, the Institute offers courses available to students both local and from abroad. An expanded institute is in the final stages of construction and should be open before the end of 2010.

The other is the Virgin Mary Mosaic Workshop. According to founder and owner Raghda, “This is the only place in Jordan that teaches women the basics of the craft. Creating mosaics was traditionally men’s work.” Handcraft is considered a viable avenue for developing small business. Raghda proudly showed us news stories on the Workshop, and photos of herself with Jordan’s popular Queen Rania. She also took the time to explain differences in quality and how to tell whether a mosaic had been made locally, or in a mechanized Syrian setting.

One possibility for volunteer work is to teach English at the New Orthodox School. This is an attractive set of buildings attached to the Church of St. George. Information is posted in the gift shop outside the church. Volunteers receive free lodging and Arabic lessons, as well as a small stipend.

Other Madaba Attractions

The city likes to consider itself a haven of Jordanian handicrafts in general. There are shops and workshops devoted to ceramics, jewelry and embroidery. Aficionados of weaving should check out the Bani Hamida project in the village of Mukawir (also the site of King Herod’s palace), started as a cooperative by a dozen women in 1985 and now selling internationally.

There is perhaps no greater attraction in Madaba than its people. Jordanians in general are famously welcoming and hospitable. In Madaba there seems to be an effective combination of sophistication (after all, there’s a steady stream of foreign visitors) built over a still-cohesive social atmosphere. The mix of religions contributes to this. A third of the town is Christian, the remainder Muslim, and churches and mosques are interspersed. Neither group can dominate, and the need to co-exist provides a relaxed air of tolerance.

|

|

This patriarch is savoring the partly-completed front room of his growing compound.

|

While the plight of Palestinians throughout the Middle East is well-documented, in Jordan things don’t feel quite so dire. Fully two-thirds of the populace is Palestinian. As locations go, Jordan is a pretty relaxed spot for travelers and locals to mingle and share each other’s worldview. While we had a number of Palestinians touch on their anguish for a homeland, we never sought to steer the conversation in that direction and, not surprisingly, we discovered that they too shared everyday concerns about quality education for their children, the scarcity of water resources, and the current round of matches in the European Champions League.

Mount Nebo

Madaba also makes a useful base to explore the surrounding area. Half an hour outside town lies Mount Nebo, the fabled spot where Moses looked out over the Promised Land. (He wasn’t allowed to enter.) This is also where Moses is said to be buried, though his tomb is unknown. There are various memorials erected, including an intriguing metal serpent/staff sculpture.

There is also a small museum. Of greatest interest to me was a rare mosaic inscription piece done in Palesto-Aramaian, the common language of the region for much of the Biblical era. And, of course, there are mosaics, including vast interior floors of ruined churches with border decorations depicting animal life and other forbidden Islamic topics. These survived an 8th century blast of iconoclasm by being covered over with geometric mosaics, which thus preserved the originals below.

On a clear day the views west from Mount Nebo carry the eye well into the Palestinian Territories and beyond, to Israel. The Dead Sea lies below, and off in the distance Jericho, and even Jerusalem, though the foreground is empty hillsides and a single winding ribbon of road.

Onwards from Madaba

If using public transport one will almost invariably need to catch a mini-bus or shared taxi into Amman, and thence onwards. But for guests at the Mariam Hotel (a mid-level accommodation that provides the best travelers’ nexus in town), there is access to the informal car service run out of the lobby by a Palestinian who used to live in Ohio.

Besides the obvious, like a taxi to or from the airport (which is actually closer to Madaba than to Amman), or down to the Dead Sea, one can arrange any number of day trips, with set prices already posted. We needed to be at the Allenby Bridge early on a Friday, in order to complete the border crossing to Israel before it shut for the weekly Shabbat, or Sabbath. Instead of a three hour journey by bus via Amman, we had a 45 minute ride. Another time we wanted to explore the King’s Highway (which has followed its hilltop path through Madaba to Egypt since the time of the pharaohs) en route to the ruins of Petra. No public transport takes that route. But thanks to our ride with Yasseem, one of the Palestinian drivers from the Mariam, we not only retraced the old caravan route, but we were able to make stops along the stunning vistas of Wadi Mujib, and further south, in the Dana Nature Reserve. We also halted to explore the forbidding bulk of Kerak Castle, a crusader fort that still dominates the town of Kerak.

And then at the end of the ride — Petra, the rose-red city, but that is another story.

If You Go

Jordan Tourism Board

Daniel Gabriel's stories and articles have appeared in over 200 publications in 8 countries, including many pieces in Transitions Abroad over the past 25+ years.

|