Living Under The Volcano in Iceland

Three Months After Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull Eruption

Article and photos by Lies Ouwerkerk

Senior Contributing Editor

|

|

Farmland under the volcano in Iceland.

|

"Must be a thunderstorm," thought Hans-Martin Moser, one of the museum guides of the Skógar Folk Museum, when he was about to close shop on the evening of April 14, 2010, and looked out of a window. The enormous red sky and accompanying heavy rumbling sounds were nothing out of the ordinary since, for people living practically next door to the Eyjafjallajökull glacier, strong forces of nature had always been a mere fact of life. Glacial rumblings were, after all, the lullabies they had grown up with.

Soon, though, civil protection officials started calling and knocking on doors throughout the area as a vast explosive eruption of the volcano under the ice cap had shot an incredible amount of smoke and steam into the air, causing torrents of melt water from the glacier to flood down the nearby rivers and onto the lowlands. The rivers rose by up to three meters, forcing folks living directly under the slope to evacuate their properties immediately and head for shelters in the nearby town of Vik. Of course, it had long been known that an active volcano was brewing underneath the picturesque glacier cap. Yet, the 1,666 meters Eyjafjallajökull had only erupted three times since Iceland's settlement date: in 920, 1612, and 1821-23. "Its peak is shrouded in ice, but fire rages below," wrote Iceland's famous poet Jónas Hallgrímsson in the early 19th century.

On March 20, 2010, there had already been a more minor volcanic eruption of the Fimmvörduháls, close to the Eyjafjallajökull glacier. It had been spewing lava for 24 days in a row, creating spectacular sights of burning red lava against the contrasting white snow and becoming a significant tourist attraction for curious onlookers from Iceland's capital, Reykjavik, about 120 kilometers more to the west. The April 14 eruption, however, was many times more powerful and violent because of the interaction with ice and water, spewing volcanic ash into the small farming communities lying directly under the volcano and into the stratosphere. A strong northern wind spread the ash clouds far toward the south, and soon, air traffic in Europe was severely disrupted for nearly a week, grounding more than 10 million air travelers worldwide. Culprit Eyjafjallajökull, having lain dormant for almost two centuries and until that point unknown to most of the world, suddenly made headlines.

|

|

Glacier in the disaster area.

|

"Maybe we were too much in shock," reflects Moser when I meet with him in the small community of Skógar three months after the eruption, "but all I could think of that night was my camera and whether I had enough batteries. I was more fascinated by the spectacle than scared of what was actually going to happen."

Reality slowly set in only in the days following the April 14 eruption. The Thorvaldseyri compound, the largest farm in the district and situated at the separation line between mountain and farmland, was totally inundated by water mixed with mud and ash and shifted at least eight centimeters in the ground. By day three, at the peak of the eruption, a large area around the volcano was covered in ash as thick as 15 cm or even more, permanently blacking out the whole district, even on a sunny day. "We lived in total darkness for days," says Margrét Einarsdóttir from the neighboring Museum of Transport and Communication, "and thick layers of dust kept penetrating our houses, even after we had sealed all the windows. When we would open the door to enter the house, birds would immediately fly in towards the light. Three months after the eruption, the tape has not yet been removed, as ash particles originating from the mountain or blown from the ground by strong winds are still floating in the air everywhere."

During the initial weeks of the eruption, Iceland's main coastal ring road was flooded entirely around Eyjafjallajökull and closed off for many kilometers. Road workers had to smash a hole in the highway to give all the water a route to the coast and prevent a significant bridge from being swept away.

Breathing masks were distributed to prevent the fine ash from penetrating the lungs of the area's farmers. They soon returned to the disaster area to care for their animals, where a string of problems created by the ash fall awaited them. All animals had to be kept inside when lambing began, and cows should have gone outside to graze the fields. Now, their lands were covered with ash and mud and contaminated by the toxic gases of the ashes. Luckily, enough hay remained to feed the cattle for one spring and summer. But as the eruption continued and the animals were kept crammed in their stables, lambs started to die in the overcrowded sheds. Finally, when grazing land outside the danger area could be borrowed, all animals were transported to safer, greener, and more spacious grounds.

The volcanic eruption lasted 40 days and ended on May 23, 2010.

Grass and barley soon started to grow from under the mud and ashes on the farmlands under the volcano. However, it cannot be used, as the far-reaching consequences of contamination are still being determined. The area was recently declared "safe" again regarding volcanic activity, while scientists keep carefully monitoring the fissures and holes in the ground for possible tremors and undercurrents. In fact, Icelanders are now more apprehensive about another potential volcanic eruption in a region northeast of Eyjafjallajökull: the much larger Katla. So far, this volcano has had a pattern of erupting twice per century, often occurring within months of an eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, to which it might be related geologically. Katla's last significant activity took place in 1918.

|

|

A child is showing mud from the flooded grasslands.

|

I asked my guide, Dórotea Siglaugsdóttir, whether the Icelandic population had been shocked by this latest natural disaster. Her answer is very matter-of-fact: "That's what can happen when you live on The Island of Fire and Ice, where snow avalanches, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and glacial floods are the order of the day. Here, we have a strong faith in fate and in the whims of Mother Nature, as well as in our own power to overcome setbacks". Oddly enough, alongside this fatalistic and yet level-headed way of thinking, many Icelanders also seem to have maintained the centuries-old belief in huldufólk (hidden people): elves, trolls, and dwarfs inhabiting rocks, hills, and mountains and possessing supernatural powers. Maybe it is unsurprising for people who grew up with Viking sagas full of gods and superheroes and spent long, dark winters in nearly complete isolation.

Upon my return to the capital, my curiosity about these contradictions drove me to the Reykjavik City Library, one of the oldest cultural institutions of the city, where I delve into books on the geography, history, and folk tales of this nation and the supposed "national character" of its inhabitants. I read about the many active volcanoes erupting every few years, some of them having submerged whole towns in lava, about lakes still inhabited by monsters, about terrible shipwrecks and rumors of gold still on the bottom of the sea, about nuns burnt alive for selling their soul to the devil, about inexplicable disappearances and humans turning into animals, and about names for sons or dóttirs as old as the Icelandic sagas themselves. I see pictures of determined, weather-beaten faces, barren rocks, lava lands without trees, and merciless winter landscapes when the sun hardly rises. And I have come to understand that practically anything is possible on this magnificent and mysterious island just under the Arctic Circle, where, despite the many natural disasters and mysterious phenomena over the years, habitation and perseverance never died out, and where still to this day a deep belief in magic can go hand in hand with a totally pragmatic approach to life's unexpected trials and tribulations.

|

|

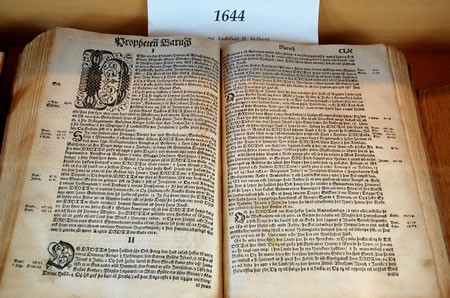

Historical treasures in the Skogar Folk Museum remained largely

untouched by the impact of the eruption.

|

Lies Ouwerkerk is originally from Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and currently lives in Montreal, Canada. Previously a columnist for The Sherbrooke Record, she is a freelance writer and photographer for various travel magazines.

|