Spirit Guardians of the Northwest Coast of Canada

The Haida Monumental Totem Poles

Article and photos by James

Michael Dorsey

|

|

Author on Ninstints

beach with totems of the Haida Nation behind

him.

|

Many of humanity's greatest artistic

achievements are unknown to the world at large because their

creators never intended for the public to view them. Among

such largely unfamiliar accomplishments are the massive

totem carvings of the Haida people, which can be found on

a windswept island group 60 miles off the coast of British

Columbia, Canada.

|

|

|

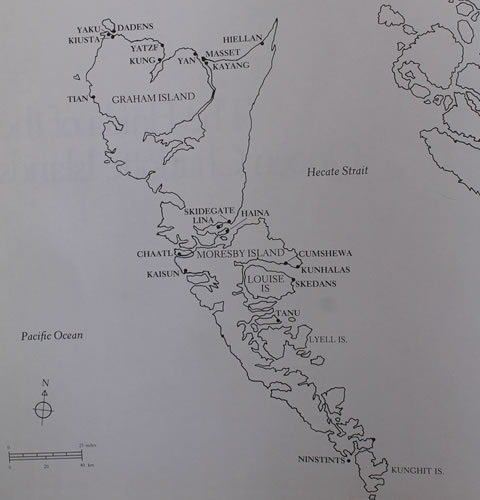

Map of the islands

of the Haida Gwaii, or "Land of the Haida," 60 miles

off the coast of British Columbia, Canada.

|

The totems watch over a sheltered cove

on the East Side of Anthony Island, at the ghost village

of Ninstints (or Skuun Gwaii, or Sung Gwaii; there are numerous

local spellings.) During my visit, 26 totem poles, with

but a handful in the world residing in their original location,

stood watch as the last mythological guardians of the Haida

Nation.

Now, this seems an appropriate time

to dispel a modern myth; American plains Indians never carved

a totem pole. Such mistaken images are yet another Hollywood

creation that originated in bad old "B movies." Totem

carving is specific to the Pacific Northwest. Most prolific

are the Haida, the native people of these islands, who carve

wood as easily as most of us breathe, and have an ancient

history rich in both art and warfare. The early people called

this land Xhaaidlagha Gwaayaai, or "Islands at the

Boundary of the World." The name has since been shortened

to Haida Gwaii, or "Land of the Haida." Most

of the world calls them by an earlier name — the Queen Charlotte

Islands. The islands number more than 1,800, and are part

of British Columbia, Canada. Their oral history can be traced

back 7,000 years. The earliest recorded information on these

islands comes from Spanish explorer, Juan Perez, who discovered

them in 1774. A decade later, Russian fur traders began

to frequent them and for the next century were the only

non-native visitors. The islands were given their British

name from the flagship of Lord Howe, the HMS Queen Charlotte,

who was the wife of King George III of England.

The totems watch over the land of the

ancestors as guardians, while also serving as both history

and literature. In Haida mythology, there are four premier

figures: Orca, Bear, Frog, and Raven. Of these, Raven takes

center stage since he is known as the trickster, always

trying to fool humankind. The Haida creation myth tells

of Raven pecking open a cockleshell to release the first

man into the world.

The story has been brought to life in

an epic carving by the northwest coast master, Bill Reid,

a descendant of Charles

Edenshaw, himself a Haida chief

named Tahayren, who later took the white name, Edenshaw.

These two men are generally acknowledged as among of the

finest carvers to ever live. Reid’s monumental carvings,

created mostly in stone, not only give life to ancient folk

tales but also rival in size and talent the early works

of such giants as Edenshaw. His finest examples may be found

in the courtyard of the Canadian Embassy in Washington D.C.

and at the Vancouver airport’s international terminal. Smaller

works by both Edenshaw and Reid now reside in some of the

world’s most prestigious museums. Today, contemporary Haida

artists carry on the tradition by carving not only wood,

but also argillite,

a dark and easily workable stone found only in a quarry

of these islands.

As a seafaring people, the Haida carved

enormous war canoes from a single cedar tree large enough

to carry dozens of warriors over 60 miles of open ocean

in order to raid and take slaves on the mainland. Their

warrior mentality earned them the title, “Vikings of the

north.” Initially, contact with white people resulted in

the introduction of metal from Russian fur traders. Metal

allowed the Haida to fashion new and more efficient tools,

increasing their skills tenfold. They carved wood on a monumental

scale. House columns, commemorative totems, burial boxes,

and even ornamental bowls were all of the highest order.

|

|

|

Old Ninstints funerary

poles.

|

Haida villages always occupied a shoreline.

The villages were surrounded by a protective midden of crushed

shells that served as a warning system against attack. The

shells outlined an intruder as a silhouette at night. At

the time, they made plenty of noise and served as an alert

when outsiders tried to sneak into their villages.

As late as the 19th century intertribal

warfare and raiding was common. Instances of ceremonial

cannibalism in which tiny pieces of the human flesh from

those vanquished in battle were consumed in order to add

the enemy's power to that of the warrior. Unfortunately,

such intertribal wars led to sensationalized news stories

attributing cannibalism to the Haida as a way of daily life,

even though that was simply not the reality.

In every Haida community, just up from

the midden’s waterline, row after row of monumental totems

told the story of the village and its history.

The poles lean now at various angles

and are deteriorating rapidly. Several funeral poles once

held wooden boxes with the remains of Haida nobles. The

early Haida buried their chiefs by packing their bodies

into tiny wooden boxes that were placed at the top of a

burial totem in front of the chief's lodge. The carvings

on the totem tell the story of significant events in the

man's life. No image is random. Each personage, whether

real or imagined, has a specific meaning: a wedding, a death,

or a great battle. The distorted faces and contorted body

positions of both man and beast on the totems suggest a

spirit world beyond the imagination of many modern people.

|

|

|

Line of many leaning

Haida totem poles.

|

At the apex of Haida culture, close

to 14,000 people occupied the islands with almost 300 living

in Ninstints. The village name is a western mispronunciation

of Nan Sdins, who was chief at the time of initial contact

with the white man. About 1860, small pox was introduced

by white fur traders and soon only about 30 people were

left alive at Ninstints. By 1911, the total native population

of all the islands stood at 589. Ninstints was totally abandoned

around 1880, but its exact date is lost to history.

Some native people believe a totem

should stand in nature until it is reclaimed by the earth.

Others have tried to save these poles for posterity. In 1995,

a large-scale restoration project was undertaken with the consent

of local Haida elders to prop up some of the poles in danger

of falling. A few have been relocated to museums. Originally,

there were 35 totems at Ninstints. At the time of my visit,

there were 26.

The old Haida villages were also always

guarded from attack by a watchman. This was an honored position

within the tribe. The watchmen were distinguished by wearing

a conical shaped hat made from cedar bark. Many of their

totems, including contemporary ones, are topped by carved

watchmen who stand guard. Today, the Haida people have reinstated

this program and each native site has an active watchman

on duty. Visitors must gain permission in advance before

landing on any of these beaches.

|

|

|

Modern Watchman

on totem.

|

In 1981, Ninstints

was declared a World Heritage Site by the UNESCO,

guaranteeing its preservation for the immediate future.

Unless these poles are removed, they will eventually

be reclaimed by time and weather, since they are organic.

For now, the remaining poles are a magnificent legacy

of a vanishing culture.

James Michael Dorsey is

an explorer, award winning author, photographer, and

lecturer. He has traveled extensively in 45 countries,

mostly far off the beaten path. His main pursuit

is visiting remote tribal cultures in Asia

and Africa.

|